60

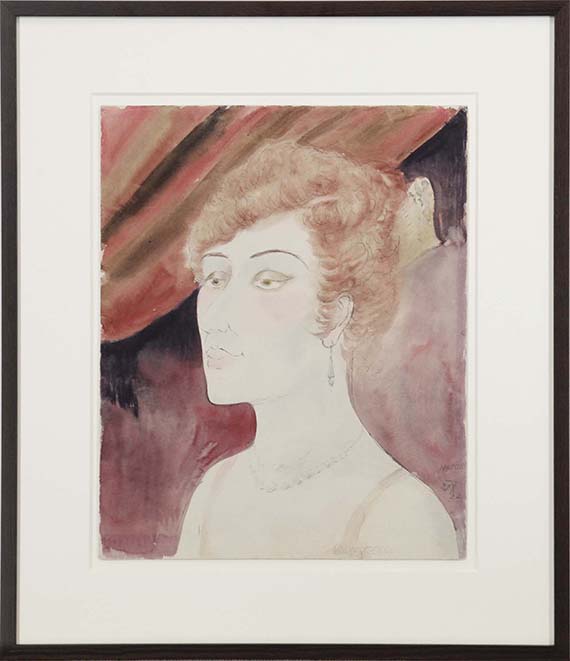

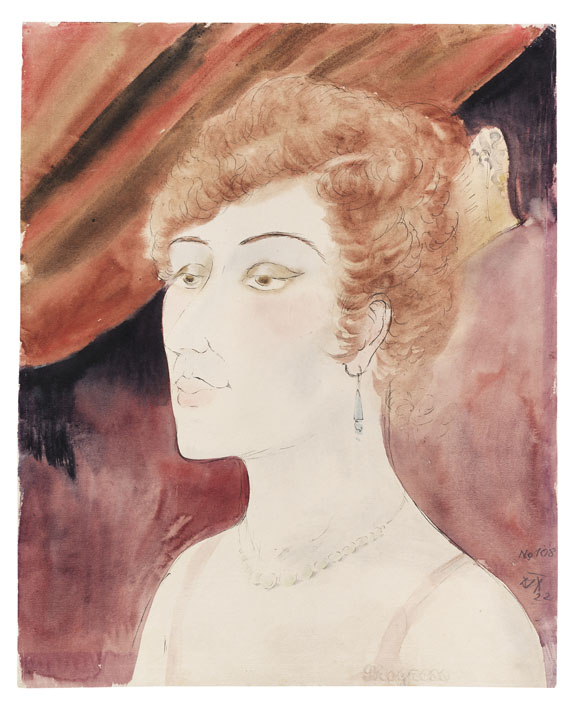

Otto Dix

Dame in der Loge, 1922.

Watercolor

Estimate:

€ 140,000 / $ 158,200 Sold:

€ 175,000 / $ 197,749 (incl. surcharge)

Dame in der Loge. 1922.

Watercolor.

Pfäffle A 1922/16. Lower right signed and dated as well as inscribed "No 108". Verso inscribed and titled by a hand other than that of the artist. On firm Progress wove paper (with embossing stamps). 49.4 x 39.8 cm (19.4 x 15.6 in), the full sheet. [CH].

• From the important Gurlitt Collection.

• Contemporary document of the eventful German history and its dram: formerly lost Jewish property, the dramatic history finds completion in a restitution.

• Glamorous demimonde: Dazzling social typology between bourgeoisie ("Dame in der Loge") and demimonde ("Dompteuse").

• Large-size watercolor from the sought-after 1920s.

PROVENANCE: Galerie Nierendorf, Cologne/Neue Kunst, Berlin (directly from the artist, verso with the hand-written number).

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, Wroclaw (verso with the fragmentarily preserved hand-written entry "L/3503/aq“).

Dr. Paul Schaefer, Wroclaw (taken over from the above, until February 26/27, 1935: auction at Max Perl, Berlin).

Prussian Secret State Police, seized (February 1935 – July 1937).

Nationalgalerie/Kronprinzenpalais, Berlin (March 1936 – July 1937, deposit).

State-owned (seized from the above in context of the "Degenerate Art" campaign in July 1937).

Hildebrand Gurlitt, Hamburg/Dresden/Aschbach (until December 5, 1945).

Neue Residenz, Bamberg (safekeeping from the possession of the above).

Central Collecting Point, Wiesbaden (from aforementioned location, verso with hand-written entry, inventory no. Wie 1977/18).

Hildebrand Gurlitt, Düsseldorf (December 15, 1950 - November 9, 1956).

Helene Gurlitt, Düsseldorf/Munich (inherited from the above, November 9, 1956 – January 31, 1968).

Cornelius Gurlitt, Munich/Salzburg (inherited from the above, January 31, 1968 – May 6, 2014).

Stiftung Kunstmuseum Bern (inherited from the above in 2014).

Restituted by Stiftung Kunstmuseum Bern to the heirs after Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer (2022).

The work is free from restitution claims.

EXHIBITION:

Bestandsaufnahme Gurlitt. „Entartete Kunst“ - Beschlagnahmt und verkauft, Kunstmuseum Bern/Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, November 2, 2017 - March 4, 2018, cat. no. 66 with color illu. on p. 194.

LITERATURE:

Willi Wolfradt, Otto Dix, in: Junge Kunst, vol. 41, Leipzig 1924, p. 33 (with illu.), also in: Der Cicerone, year XVI., 1924, pp. 943ff.

Max Perl, Bücher des 15.-20. Jahrhunderts (…), Gemälde, Aquarelle, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Kunstgewerbe, Plastik, auction on February 26 - 28, 1935 (catalog no. 188), lot 2090 (as "Brustbild einer Frau“).

Brigid S. Barton, Otto Dix und die neue Sachlichkeit 1918-1925 (PhD thesis), Michigan 1981, p. 141, V B 50.

Suse Pfäffle, Otto. Dix. Werkverzeichnis der Aquarelle und Gouachen, Stuttgart 1991, p. 151 (with illu.).

Annegret Janda, Jörn Grabowski, Kunst in Deutschland 1905-1937. Die verlorene Sammlung der Nationalgalerie, Berlin 1992, p. 96, cat. no. 66.

www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/e/db_entart_kunst/datenbank (not in NS inventory, no.: 17791-E, as "Brustbild einer Frau“).

Ira Mazzoni, Veröffentlichte Werke aus der Sammlung Gurlitt - Neue Probleme nach der Weltwirtschaftskrise, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 13, 2013.

Tim Ackermann, Kunstmuseum Bern - Das Ende des Falls Gurlitt naht, in: Weltkunst, December 10, 2021.

Mark Siemons, Gurlitt-Sammlung in Bern - Ein neuer Maßstab für Restitutionen, in: FAZ from December 15, 2021.

Isabel Pfaff, Raubkunst in der Schweiz - Goldstandard, in: SZ from December 15, 2021.

Hannah McGivern, Swiss museum to part with 29 works from Gurlitt trove suspected of being Nazi loot, in: The Art Newspaper from December 17, 2021.

Ellionor Landmann, Kunstmuseum Bern gibt Dix-Aquarelle aus Gurlitt-Kunstfund zurück, in: SRF from December 10, 2021 (broadcast).

Joachim Görgen (ARD studio Geneva), Beutekunst-Debatte in der Schweiz. Zurückgeben oder weiter ausstellen?, in Tageschau from December 29, 2021

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, print inventory, no. 3503.

Deutsches Kunstarchiv, Nuremberg, NL Otto Dix, I-B 12, exhibition documentation.

Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin, acquisition index, no. 872-338.

SMB-ZA, I/NG 826, Bl. 257-258r/v, Dr. Gotthardt/Greiser, Prussian Secret State Police, Secret Police Office, to Dr. Eberhardt Hanfstaegl, Berlin, February 19, 1936.

SMB-ZA, I/NG 826, M 12, ll. 261-270, l. 262, Dr. Eberhard Hanfstaengl to Prussian Secret State Police, Berlin, March 24, 1936.

SMB-ZA, IV/NL Rave 095, Paul Ortwin Rave to Reich Ministry of Science, Education and Culture [Bernhard Rust], Berlin, July 8, 1937.

SMB-ZA, IV/NL Rave 095, Paul Ortwin Rave to Adolf Ziegler, president of Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, Berlin, July 9, 1937.

U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG 260, Central Collecting Point, Wiesbaden, Property Card „WIE 1977/18“, December 5, 1945.

U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG 260, M1947, Claim [Germany] – Gurlitt, Hildebrand, 1946-1950, outlet list p. 15 & transfer list Neue Residenz, p. 24.

Watercolor.

Pfäffle A 1922/16. Lower right signed and dated as well as inscribed "No 108". Verso inscribed and titled by a hand other than that of the artist. On firm Progress wove paper (with embossing stamps). 49.4 x 39.8 cm (19.4 x 15.6 in), the full sheet. [CH].

• From the important Gurlitt Collection.

• Contemporary document of the eventful German history and its dram: formerly lost Jewish property, the dramatic history finds completion in a restitution.

• Glamorous demimonde: Dazzling social typology between bourgeoisie ("Dame in der Loge") and demimonde ("Dompteuse").

• Large-size watercolor from the sought-after 1920s.

PROVENANCE: Galerie Nierendorf, Cologne/Neue Kunst, Berlin (directly from the artist, verso with the hand-written number).

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, Wroclaw (verso with the fragmentarily preserved hand-written entry "L/3503/aq“).

Dr. Paul Schaefer, Wroclaw (taken over from the above, until February 26/27, 1935: auction at Max Perl, Berlin).

Prussian Secret State Police, seized (February 1935 – July 1937).

Nationalgalerie/Kronprinzenpalais, Berlin (March 1936 – July 1937, deposit).

State-owned (seized from the above in context of the "Degenerate Art" campaign in July 1937).

Hildebrand Gurlitt, Hamburg/Dresden/Aschbach (until December 5, 1945).

Neue Residenz, Bamberg (safekeeping from the possession of the above).

Central Collecting Point, Wiesbaden (from aforementioned location, verso with hand-written entry, inventory no. Wie 1977/18).

Hildebrand Gurlitt, Düsseldorf (December 15, 1950 - November 9, 1956).

Helene Gurlitt, Düsseldorf/Munich (inherited from the above, November 9, 1956 – January 31, 1968).

Cornelius Gurlitt, Munich/Salzburg (inherited from the above, January 31, 1968 – May 6, 2014).

Stiftung Kunstmuseum Bern (inherited from the above in 2014).

Restituted by Stiftung Kunstmuseum Bern to the heirs after Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer (2022).

The work is free from restitution claims.

EXHIBITION:

Bestandsaufnahme Gurlitt. „Entartete Kunst“ - Beschlagnahmt und verkauft, Kunstmuseum Bern/Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, November 2, 2017 - March 4, 2018, cat. no. 66 with color illu. on p. 194.

LITERATURE:

Willi Wolfradt, Otto Dix, in: Junge Kunst, vol. 41, Leipzig 1924, p. 33 (with illu.), also in: Der Cicerone, year XVI., 1924, pp. 943ff.

Max Perl, Bücher des 15.-20. Jahrhunderts (…), Gemälde, Aquarelle, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Kunstgewerbe, Plastik, auction on February 26 - 28, 1935 (catalog no. 188), lot 2090 (as "Brustbild einer Frau“).

Brigid S. Barton, Otto Dix und die neue Sachlichkeit 1918-1925 (PhD thesis), Michigan 1981, p. 141, V B 50.

Suse Pfäffle, Otto. Dix. Werkverzeichnis der Aquarelle und Gouachen, Stuttgart 1991, p. 151 (with illu.).

Annegret Janda, Jörn Grabowski, Kunst in Deutschland 1905-1937. Die verlorene Sammlung der Nationalgalerie, Berlin 1992, p. 96, cat. no. 66.

www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/e/db_entart_kunst/datenbank (not in NS inventory, no.: 17791-E, as "Brustbild einer Frau“).

Ira Mazzoni, Veröffentlichte Werke aus der Sammlung Gurlitt - Neue Probleme nach der Weltwirtschaftskrise, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 13, 2013.

Tim Ackermann, Kunstmuseum Bern - Das Ende des Falls Gurlitt naht, in: Weltkunst, December 10, 2021.

Mark Siemons, Gurlitt-Sammlung in Bern - Ein neuer Maßstab für Restitutionen, in: FAZ from December 15, 2021.

Isabel Pfaff, Raubkunst in der Schweiz - Goldstandard, in: SZ from December 15, 2021.

Hannah McGivern, Swiss museum to part with 29 works from Gurlitt trove suspected of being Nazi loot, in: The Art Newspaper from December 17, 2021.

Ellionor Landmann, Kunstmuseum Bern gibt Dix-Aquarelle aus Gurlitt-Kunstfund zurück, in: SRF from December 10, 2021 (broadcast).

Joachim Görgen (ARD studio Geneva), Beutekunst-Debatte in der Schweiz. Zurückgeben oder weiter ausstellen?, in Tageschau from December 29, 2021

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Collection Dr. Ismar Littmann, print inventory, no. 3503.

Deutsches Kunstarchiv, Nuremberg, NL Otto Dix, I-B 12, exhibition documentation.

Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin, acquisition index, no. 872-338.

SMB-ZA, I/NG 826, Bl. 257-258r/v, Dr. Gotthardt/Greiser, Prussian Secret State Police, Secret Police Office, to Dr. Eberhardt Hanfstaegl, Berlin, February 19, 1936.

SMB-ZA, I/NG 826, M 12, ll. 261-270, l. 262, Dr. Eberhard Hanfstaengl to Prussian Secret State Police, Berlin, March 24, 1936.

SMB-ZA, IV/NL Rave 095, Paul Ortwin Rave to Reich Ministry of Science, Education and Culture [Bernhard Rust], Berlin, July 8, 1937.

SMB-ZA, IV/NL Rave 095, Paul Ortwin Rave to Adolf Ziegler, president of Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, Berlin, July 9, 1937.

U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG 260, Central Collecting Point, Wiesbaden, Property Card „WIE 1977/18“, December 5, 1945.

U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG 260, M1947, Claim [Germany] – Gurlitt, Hildebrand, 1946-1950, outlet list p. 15 & transfer list Neue Residenz, p. 24.

Watching theater boxes through small opera glasses from a safe distance has been a common parlor game since the mid-19th century. In 1874, Eduard Manet observed a couple who were waiting in very different ways for the performance to begin: the lady, dressed conspicuously in a black and white robe and adorned with plenty of jewellery, seems to be staring at the stage, while the man at her side voyeuristically looks at the boxes above him with the opera glasses. For Mary Cassatt, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec or Honoré Daumier, for example, the discovery of opera glasses became an iconographic eye-catcher and attracted the attention of the viewer in many scenes, albeit not as key theme.

Otto Dix also seems to use these barely conspicuous opera glasses for his purposes and discovers our "Dame", this striking appearance in a box lavishly furnished with red velvet during a performance. With a fine drawing he describes the body lines around the nose and shoulder-free décolleté, emphasizes the full lips with little use of delicate watercolor paint, draws the contours of the eyes and eyebrows, adds the fine jewelry, earrings and necklace, fine pen and ink emphasize the physiognomy. Her fine, curly, red hair is pinned up, the hairstyle emphasized with a conspicuous comb at the back of her head. Concentrating on what is happening, the elegant lady in evening dress does not seem to notice the artist's fixation. For him, however, beauty appears full of sensuality, and with this the erotic features of a whore are emphasized. The "Dame in der Loge" is aware of her lustful, demonic power, and the artist emphasizes this in his fine way of drawing. Is it actually a box in a theater or opera house, or does the artist see the lady in an establishment lavishly furnished with plush and velvet? Nevertheless, the artist leaves the viewer in the dark with the numerous allusions.

After the end of the First World War, Otto Dix felt the urge to return to Dresden, to the city and to his artist friends. On a cold February day in 1919, he drove to the Saxon capital, standing on the footboard of an overcrowded railway wagon. He moved into his old student apartment and began to remember his former student and artist life. However, the experiences of war introduced a new theme into his work, the horrors of war. Back in Dresden, he also took up the theme of beautiful Eros, the human primal instinct, which the artist not only enjoys formally.

At this time, however, an increase in the thematization of Eros can be observed not only in Dix, but in the art of his time in general, such as it is the case with George Grosz. Despite the exuberant dramatization of the events, Dix, emotionally charged by his experiences, manages with an astonishing objectivity, looking at the dazzling motifs like a contemporary witness with some distance. The arrangement now seems somewhat anonymous, often ironic and yet naively direct. “Rediscovering the bad experiences of the front stage as a behavioral norm in post-war Germany down to the deepest provincial corners, together with the war experience itself, provokes cynical sarcasm. Dix responds to the disinhibition in eroticism and the perversion of heroism in the civil war, as well as to the degeneration of the economy, the profiteers from war and inflation, with a mercilessly plebeian disillusionment with eros, heroes and power,” says art historian Diether Schmidt. (ibid. p. 50) The work of Otto Dix of the 1920s shows a broad spectrum from Verism, Surrealism to New Objectivity.

An eventful history

When the "Schwabing Art Trove ", which was discovered in 2012, was presented to the public in January 2013 accompanied by broad media coverage, the two Dix watercolors "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" from 1922 also moved to the centerof attention. Soon indications were found that the sheets, which Cornelius Gurlitt had taken over from the inventory of his father, the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, were originally from the collection of the famous Jewish lawyer and notary Dr. Ismar Littmann from Breslau. This origin also ennobles these works: Littmann was one of the most active and most important collectors of German Expressionist art.

Born on July 2, 1878 as a merchant's son in Groß Strehlitz in Upper Silesia, he settled in Breslau in 1906, where he soon married Käthe Fränkel. Ismar Littmann was admitted to the district court as a lawyer. He soon ran his own law firm, later together with his partner Max Loewe, and was promoted to notary in 1921. The wealthy lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann was a generous patron and supporter of modern, progressive art. He was particularly committed to contemporary artists associated with the Academy of Fine Arts in Breslau, such as the "Brücke" painter and academy professor Otto Mueller. The proverbial “Bohemian artists from Breslau” is what Ismar Littmann shapes, promotes and accompanies as a collector and patron.

Beginning in the late 1910s, Dr. Ismar Littmann build up his soon to be famous art collection. The Littmann Collection includes works by well-known German artists of Impressionism and Expressionism, including Otto Dix, Otto Mueller, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Alexander Kanoldt and Lovis Corinth. Littmann had a close personal connection to some of those named. It was not until the global economic crisis in 1929 that the passion for collecting came to an end. By then, Littmann had collected almost 6,000 important works of art, watercolors, drawings and prints as well as paintings. In order to compensate for economic bottlenecks, Dr. Ismar Littmann offered parts of his collection at Paul Graupe's auction in Berlin on March 21, 1932. Among them was the work "Dompteuse", however, as the conditions for sales were difficult at that time, remained unsold and returned to the ownership of the collector.

Nevertheless: Littmann's economic worries in 1932 were not existential yet. Only the "seizure of power" by the National Socialists brought about abrupt change. The persecution of the Jewish lawyer began early and with great severity. His professional group was one of the first to be economically and socially destroyed by the National Socialists. From the spring of 1933, neither Dr. Ismar Littmann nor his son Hans (Edward) Littmann were able to pursue their profession. The youngest daughter Ruth could not even finish her high school exams, because she was arrested as she protested against the regime. Still a minor, she was put in prison for a year before she was able to emigrate to Israel. Deprived of his livelihood and joie de vivre, Ismar Littmann faced the ruins of a once glorious existence. Deep despair drove him to suicide on September 23, 1934. Ismar Littmann left behind his widow Käthe and their four children. With luck, the survivors were able to flee from National Socialist dictatorship.

Before despair drove the Breslau lawyer to suicide, Dr. Ismar Littmann was forced to sell a large bundle of almost 3,600 works of his graphics or to use them as security for a loan. His friend, the Breslau dentist Dr. Paul Schaefer, supported Littmann and took the works over. It is not known whether Schaefer actually acquired the paintings or whether they were merely a security for a loan from Schaefer to Littmann. In any case, Schaefer himself was not a collector, taking over the graphic works was a mere gesture of friendship.

The lots taken over by Paul Schaefer also contained the two Otto Dix watercolors "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" offered here. As a consignment by Paul Schaefer, who as a Jew was also persecuted by the National Socialists and was later forced to flee to South America with his wife, the watercolors were offered in the famous auction of the Littmann Collection at Max Perl in February 1935. It can be assumed that Schaefer was the owner, but not the owner of the sheets, because unsold works from his consignment at Perl did not go back to Schaefer after the auction, but to Käthe Littmann. Our two works of art, however, have a different fate – they never even got to the point where they were called up in the auction.

The auction at Perl went down in history. As early as in 1935, the discussion about so-called “degenerate art” flared up. 64 paintings, watercolors and drawings were confiscated by the Gestapo before the auction as examples of “cultural Bolshevik tendencies” and sent to the Berlin National Gallery the following year. Its director at the time, Eberhard Hanfstaengl, kept some of the works as "contemporary documents" and had the rest of them burned in the furnace of the Kronprinzenpalais on March 23, 1936 by order of the Gestapo (cf. Annegret Janda, Das Schicksal einer Sammlung, 1986, p. 69). Sources show that "Dame in der Loge" was also confiscated by the Gestapo in 1935 from the auction house's premises. There is a high probability that "Dompteuse" shared the fate. As part of the "Perl portfolio", the watercolors were confiscated again on July 7, 1937 as part of the "Degenerate Art" confiscation campaign, this time from the National Gallery. With a lot of luck, the two Dix works escaped destruction through the National Socialist rulers a second time – and ended up in the hands of Hildebrand Gurlitt.

When exactly he acquired the two watercolors can no longer be reconstructed today. In any case, from around the end of 1938, Gurlitt was one of the four art dealers (along with Böhmer, Buchholz and Möller) who had access to the National Socialist depots in Schönhausen. In the period between 1939 and 1941, several commission and barter transactions took place, in which he probably took over the two watercolors, among other things. However, he did not sell them, but kept them as part of the remainder of his art trade, which later became the "Schwabing Art Trove". The sheets thus ended up in the Gurlitt estate and were discovered in Munich in 2012.

In 2014, the Foundation of the Kunstmuseum Bern became the sole heir to this collection, which attracted international attention. The research of the task force on "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" was actively continued. “We are extremely grateful to the Kunstmuseum Bern for taking this step. It is extraordinary that a museum spares no expense or effort to process the history of the works," said the heirs of Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer commenting on the museum's own initiative.

However, the decades that have passed and the turmoil of war have left gaps in the records that can no longer be closed, even with the greatest care. In 2021, the museum decides, despite a history of loss that can no longer be reconstructed down to the last detail, to jointly hand over the two works of art by Otto Dix to the heirs of Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer - thereby setting new standards for a proactive and responsible handling of art looted by the Nazis. [MvL/SvdL/AT]

Otto Dix also seems to use these barely conspicuous opera glasses for his purposes and discovers our "Dame", this striking appearance in a box lavishly furnished with red velvet during a performance. With a fine drawing he describes the body lines around the nose and shoulder-free décolleté, emphasizes the full lips with little use of delicate watercolor paint, draws the contours of the eyes and eyebrows, adds the fine jewelry, earrings and necklace, fine pen and ink emphasize the physiognomy. Her fine, curly, red hair is pinned up, the hairstyle emphasized with a conspicuous comb at the back of her head. Concentrating on what is happening, the elegant lady in evening dress does not seem to notice the artist's fixation. For him, however, beauty appears full of sensuality, and with this the erotic features of a whore are emphasized. The "Dame in der Loge" is aware of her lustful, demonic power, and the artist emphasizes this in his fine way of drawing. Is it actually a box in a theater or opera house, or does the artist see the lady in an establishment lavishly furnished with plush and velvet? Nevertheless, the artist leaves the viewer in the dark with the numerous allusions.

After the end of the First World War, Otto Dix felt the urge to return to Dresden, to the city and to his artist friends. On a cold February day in 1919, he drove to the Saxon capital, standing on the footboard of an overcrowded railway wagon. He moved into his old student apartment and began to remember his former student and artist life. However, the experiences of war introduced a new theme into his work, the horrors of war. Back in Dresden, he also took up the theme of beautiful Eros, the human primal instinct, which the artist not only enjoys formally.

At this time, however, an increase in the thematization of Eros can be observed not only in Dix, but in the art of his time in general, such as it is the case with George Grosz. Despite the exuberant dramatization of the events, Dix, emotionally charged by his experiences, manages with an astonishing objectivity, looking at the dazzling motifs like a contemporary witness with some distance. The arrangement now seems somewhat anonymous, often ironic and yet naively direct. “Rediscovering the bad experiences of the front stage as a behavioral norm in post-war Germany down to the deepest provincial corners, together with the war experience itself, provokes cynical sarcasm. Dix responds to the disinhibition in eroticism and the perversion of heroism in the civil war, as well as to the degeneration of the economy, the profiteers from war and inflation, with a mercilessly plebeian disillusionment with eros, heroes and power,” says art historian Diether Schmidt. (ibid. p. 50) The work of Otto Dix of the 1920s shows a broad spectrum from Verism, Surrealism to New Objectivity.

An eventful history

When the "Schwabing Art Trove ", which was discovered in 2012, was presented to the public in January 2013 accompanied by broad media coverage, the two Dix watercolors "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" from 1922 also moved to the centerof attention. Soon indications were found that the sheets, which Cornelius Gurlitt had taken over from the inventory of his father, the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, were originally from the collection of the famous Jewish lawyer and notary Dr. Ismar Littmann from Breslau. This origin also ennobles these works: Littmann was one of the most active and most important collectors of German Expressionist art.

Born on July 2, 1878 as a merchant's son in Groß Strehlitz in Upper Silesia, he settled in Breslau in 1906, where he soon married Käthe Fränkel. Ismar Littmann was admitted to the district court as a lawyer. He soon ran his own law firm, later together with his partner Max Loewe, and was promoted to notary in 1921. The wealthy lawyer Dr. Ismar Littmann was a generous patron and supporter of modern, progressive art. He was particularly committed to contemporary artists associated with the Academy of Fine Arts in Breslau, such as the "Brücke" painter and academy professor Otto Mueller. The proverbial “Bohemian artists from Breslau” is what Ismar Littmann shapes, promotes and accompanies as a collector and patron.

Beginning in the late 1910s, Dr. Ismar Littmann build up his soon to be famous art collection. The Littmann Collection includes works by well-known German artists of Impressionism and Expressionism, including Otto Dix, Otto Mueller, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Alexander Kanoldt and Lovis Corinth. Littmann had a close personal connection to some of those named. It was not until the global economic crisis in 1929 that the passion for collecting came to an end. By then, Littmann had collected almost 6,000 important works of art, watercolors, drawings and prints as well as paintings. In order to compensate for economic bottlenecks, Dr. Ismar Littmann offered parts of his collection at Paul Graupe's auction in Berlin on March 21, 1932. Among them was the work "Dompteuse", however, as the conditions for sales were difficult at that time, remained unsold and returned to the ownership of the collector.

Nevertheless: Littmann's economic worries in 1932 were not existential yet. Only the "seizure of power" by the National Socialists brought about abrupt change. The persecution of the Jewish lawyer began early and with great severity. His professional group was one of the first to be economically and socially destroyed by the National Socialists. From the spring of 1933, neither Dr. Ismar Littmann nor his son Hans (Edward) Littmann were able to pursue their profession. The youngest daughter Ruth could not even finish her high school exams, because she was arrested as she protested against the regime. Still a minor, she was put in prison for a year before she was able to emigrate to Israel. Deprived of his livelihood and joie de vivre, Ismar Littmann faced the ruins of a once glorious existence. Deep despair drove him to suicide on September 23, 1934. Ismar Littmann left behind his widow Käthe and their four children. With luck, the survivors were able to flee from National Socialist dictatorship.

Before despair drove the Breslau lawyer to suicide, Dr. Ismar Littmann was forced to sell a large bundle of almost 3,600 works of his graphics or to use them as security for a loan. His friend, the Breslau dentist Dr. Paul Schaefer, supported Littmann and took the works over. It is not known whether Schaefer actually acquired the paintings or whether they were merely a security for a loan from Schaefer to Littmann. In any case, Schaefer himself was not a collector, taking over the graphic works was a mere gesture of friendship.

The lots taken over by Paul Schaefer also contained the two Otto Dix watercolors "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" offered here. As a consignment by Paul Schaefer, who as a Jew was also persecuted by the National Socialists and was later forced to flee to South America with his wife, the watercolors were offered in the famous auction of the Littmann Collection at Max Perl in February 1935. It can be assumed that Schaefer was the owner, but not the owner of the sheets, because unsold works from his consignment at Perl did not go back to Schaefer after the auction, but to Käthe Littmann. Our two works of art, however, have a different fate – they never even got to the point where they were called up in the auction.

The auction at Perl went down in history. As early as in 1935, the discussion about so-called “degenerate art” flared up. 64 paintings, watercolors and drawings were confiscated by the Gestapo before the auction as examples of “cultural Bolshevik tendencies” and sent to the Berlin National Gallery the following year. Its director at the time, Eberhard Hanfstaengl, kept some of the works as "contemporary documents" and had the rest of them burned in the furnace of the Kronprinzenpalais on March 23, 1936 by order of the Gestapo (cf. Annegret Janda, Das Schicksal einer Sammlung, 1986, p. 69). Sources show that "Dame in der Loge" was also confiscated by the Gestapo in 1935 from the auction house's premises. There is a high probability that "Dompteuse" shared the fate. As part of the "Perl portfolio", the watercolors were confiscated again on July 7, 1937 as part of the "Degenerate Art" confiscation campaign, this time from the National Gallery. With a lot of luck, the two Dix works escaped destruction through the National Socialist rulers a second time – and ended up in the hands of Hildebrand Gurlitt.

When exactly he acquired the two watercolors can no longer be reconstructed today. In any case, from around the end of 1938, Gurlitt was one of the four art dealers (along with Böhmer, Buchholz and Möller) who had access to the National Socialist depots in Schönhausen. In the period between 1939 and 1941, several commission and barter transactions took place, in which he probably took over the two watercolors, among other things. However, he did not sell them, but kept them as part of the remainder of his art trade, which later became the "Schwabing Art Trove". The sheets thus ended up in the Gurlitt estate and were discovered in Munich in 2012.

In 2014, the Foundation of the Kunstmuseum Bern became the sole heir to this collection, which attracted international attention. The research of the task force on "Dame in der Loge" and "Dompteuse" was actively continued. “We are extremely grateful to the Kunstmuseum Bern for taking this step. It is extraordinary that a museum spares no expense or effort to process the history of the works," said the heirs of Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer commenting on the museum's own initiative.

However, the decades that have passed and the turmoil of war have left gaps in the records that can no longer be closed, even with the greatest care. In 2021, the museum decides, despite a history of loss that can no longer be reconstructed down to the last detail, to jointly hand over the two works of art by Otto Dix to the heirs of Dr. Ismar Littmann and the granddaughter of Dr. Paul Schaefer - thereby setting new standards for a proactive and responsible handling of art looted by the Nazis. [MvL/SvdL/AT]

60

Otto Dix

Dame in der Loge, 1922.

Watercolor

Estimate:

€ 140,000 / $ 158,200 Sold:

€ 175,000 / $ 197,749 (incl. surcharge)

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.

Lot 60

Lot 60