436

Gabriele Münter

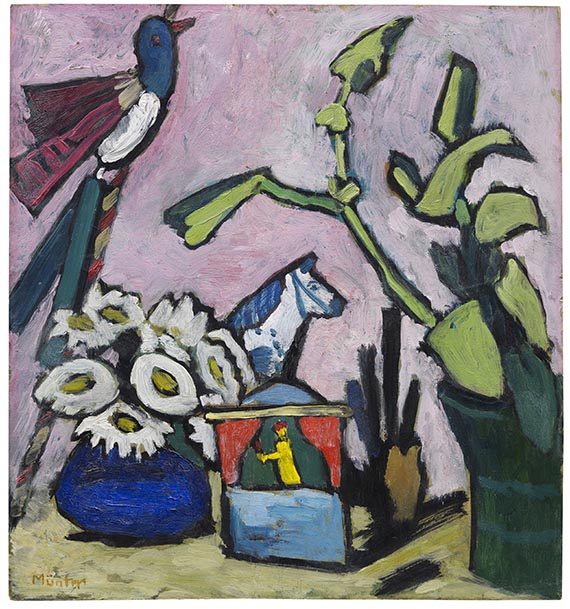

Stilleben mit Kasperltheater, 1917.

Oil on cardboard

Estimate:

€ 80,000 / $ 92,800 Sold:

€ 95,250 / $ 110,489 (incl. surcharge)

436

Gabriele Münter

Stilleben mit Kasperltheater, 1917.

Oil on cardboard

Estimate:

€ 80,000 / $ 92,800 Sold:

€ 95,250 / $ 110,489 (incl. surcharge)

Stilleben mit Kasperltheater. 1917.

Oil on cardboard.

Lower left signed. Verso with the estate stamp. 37 x 34.5 cm (14.5 x 13.5 in). [EH].

• From 1917, a year of particular significance for the artist, both in terms of her private and professional life.

• In this still life, the observer can experience Gabriele Münters personal living environment.

• Works from this period can be found in, among others, the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo, the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio and the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

• With this subject, the artist reached her goal of an artistic reorientation towards a stronger simplification of the form and clearer and brighter colors during her Scandinavian creative period (1915-1920).

• Part of the smae private collection for more than fourty years.

Accompanied by a written expertise issued by the Gabriele Münter- and Johannes Eichner-Foundation, Munich, from 8 August, 2023. The work will be included into the catalog raisonné of paintings by Gabriele Münter.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (with the stamp on the reverse).

Art trade Munich/Campione d’Italia.

Galleria Henze, Campione d’Italia (acquired from the above).

Privatsammlung Bayern (acquired from the above in 1979).

Ever since family-owned.

"She captures what escapes others, things that are to quiet to be said.“

Gregor Poulsson about Gabriele Münter's painting, in: Stockholms Dagblad, October 20, 1916, quoted from: Ex. cat. Gabriele Münter, Munich/Frankfurt a. M./Stockholm 1992, p. 73.

"I portray the world as it essentially appears to me."

Gabriele Münter in an article for the magazine "Das Kunstwerk" in retrospect in 1948, quoted from: Karoline Hille, Gabriele Münter. Die Künstlerin mit der Zauberhand, p. 12.

Oil on cardboard.

Lower left signed. Verso with the estate stamp. 37 x 34.5 cm (14.5 x 13.5 in). [EH].

• From 1917, a year of particular significance for the artist, both in terms of her private and professional life.

• In this still life, the observer can experience Gabriele Münters personal living environment.

• Works from this period can be found in, among others, the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo, the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio and the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

• With this subject, the artist reached her goal of an artistic reorientation towards a stronger simplification of the form and clearer and brighter colors during her Scandinavian creative period (1915-1920).

• Part of the smae private collection for more than fourty years.

Accompanied by a written expertise issued by the Gabriele Münter- and Johannes Eichner-Foundation, Munich, from 8 August, 2023. The work will be included into the catalog raisonné of paintings by Gabriele Münter.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (with the stamp on the reverse).

Art trade Munich/Campione d’Italia.

Galleria Henze, Campione d’Italia (acquired from the above).

Privatsammlung Bayern (acquired from the above in 1979).

Ever since family-owned.

"She captures what escapes others, things that are to quiet to be said.“

Gregor Poulsson about Gabriele Münter's painting, in: Stockholms Dagblad, October 20, 1916, quoted from: Ex. cat. Gabriele Münter, Munich/Frankfurt a. M./Stockholm 1992, p. 73.

"I portray the world as it essentially appears to me."

Gabriele Münter in an article for the magazine "Das Kunstwerk" in retrospect in 1948, quoted from: Karoline Hille, Gabriele Münter. Die Künstlerin mit der Zauberhand, p. 12.

From Staffelsee to the Stockholm Archipelago: Relocation and Transformation

Gabriele Münter's five years in Scandinavia,decisively differed from the previous happy-go-lucky years in Murnau before the First World War, both in private and artistic terms. On the one hand, she finally broke up with her long-time partner Wassily Kandinsky, on the other hand, her work underwent a clear stylistic change and helped her to greater fame and successful solo and group exhibitions in Scandinavia. In the spring of 1918, for example, her largest solo exhibition to date took place in "Den Frie Udstilling" in Copenhagen. The exhibition mainly showed new works created in Scandinavia and attracted more than 600 visitors a day.

In the spring of 1915, the artist had cleared her apartment on Ainmillerstraße in Munich and, after brief stays in Berlin and Copenhagen, finally moved to Stockholm. In politically neutral Sweden, in view of the raging First World War, she hoped for more frequent meetings with Kandinsky, who was living in Moscow at the time. In addition, the sister-in-law of her Berlin gallery owner Herwarth Walden was living in Scandinavia and thus offered Münter a welcome, almost family-like contact. In Stockholm, she managed to gain a foothold surprisingly quickly and established important contacts in the local art scene. "It seems to me that I have not yet seen anything as beautiful, as congenial as Stockholm. Like a better world.", the painter notes on her first evening in Stockholm (quoted from: Karoline Hille, Gabriele Münter. Die Künstlerin mit der Zauberhand, p. 137). She made friends with the painter couple Sigrid Hjertén and Isaac Grünewald and other Swedish painters, and was able to organize several solo and group exhibitions for herself and also for Kandinsky, while her works continued to be shown at the renowned gallery "Der Sturm" in Berlin.

The young painters living and working in Sweden and Denmark, whom Gabriele Münter met during these years, were strongly influenced by Henri Matisse and contemporary French painting. Having completed their training at the Académie Matisse in Paris, many of them took their impressions of French modernism when they returned to Scandinavia, where a so-called decorative expressionism was now gaining ground. It was in these circles that Münter learned the Swedish language, which she soon mastered almost flawlessly in reading and writing, and occupied herself with Swedish culture, among other things on extended trips to northern Sweden.

From the Statuette of the Virgin Mary to the 'Dala Horse'. Gabriele Münter's Passionate Interest in Folk Art

While still in Russia, Kandinsky developed a keen interest in folk art and brought a figure of the Madonna with Child and Crown with Double Cross back to Germany, which is depicted in several Münter paintings. In the years that followed, folk art played an important role in the artistic development of the 'Blauer Reiter', in the works of Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, and also in Gabriele Münter's painting. The artists were impressed by the naivety and originality, the strong colors and the simple, unadorned formal language. In Murnau, Münter and Kandinsky discovered regional reverse glass painting and also began to collect folk sculptures, contemporary nativity figures, crucifixes, statues of the Virgin Mary, votive tablets, as well as back to Germany as well as wooden and clay toys. Although Gabriele Münter certainly had only taken a few individual objects with her to Scandinavia, the work offered here reveals a small radiant light blue wooden toy that, upon closer inspection, turns out to be the ‘Punch and Judy Show’ from Gabriele Münter’s and Wassily Kandinsky's private collection (circa 1900, today in the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich).

Quite as if she also wanted to build a motivic bridge from her creative years in Germany to her artistic production in Scandinavia, the head of a compact, white, painted wooden horse can be seen in our painting in addition to the German wooden toy. It is a traditional Swedish 'Dala horse (Dalahäst)' made of pine wood, which has been made in the province of Dalarna since the 17th century. Today, the horses usually come in red, but in the early 20th century, the horses used to be mostly white, with saddle and bridle painted on them. The horse first appeared in one of Münter's paintings in the spring of 1916 and was also depicted in other paintings, drawings. and one print in the years that followed.

Münter completed the present composition with imaginative ingenuity and compositional finesse with a large green vase with leaves stylized into geometric forms protruding above the arrangement on the right, as well as an object with a colorful bird figure stretched across the height of the picture in the left margin. In the center of the table we see a small blue spherical vase with a bouquet of white flowers and another, shadowed vessel which possibly holds an assortment of different brushes, thus indicating her activity as a painter.

The impression that the objects are placed next to one another incoherently is not confirmed after closer inspection; instead it is a carefully designed, refined composition. There is nothing left of the quite spiritualized Madonna depictions of the Murnau years in her Scandinavian still lifes. The artist began to use the still life to express her more developed and renewed artistic goals: she uses bright, radiant colors, simple, almost geometrical forms, clearly stronger, darker contours, and a particularly curved, decorative line, which can also be found in other still lifes and interior scenes of these years (see illustration).

From the 'Blauer Reiter' to Artistic Independence

After just a single visit to Stockholm, Kandinsky returned to Russia in March 1916, taking a train to Moscow at six in the morning. He kept postponing a second visit until contact between the former couple finally broke off completely - Münter and Kandinsky would never see each other again. In the year the present work was created, only a few months after his visit to Stockholm, Kandinsky married a young Russian woman. Many years later, the artist wrote in a letter to a friend in Sweden: "From 1916 I was no longer a part of his life. After his return from Stockholm at that time, he remained in Russia, kept silent and married a Russian woman. In doing so, he violated the commitment he made in Stockholm, and his principle that our marriage was sacred and that it only needed conscience and not official documents. For me, his unfaithfulness to himself and to me was inconceivable and a heavy blow." (Letter to Carl Palme, March 12, 1949, quoted after: Ex. cat. 1992, p. 69).

In the months that followed, Münter not only had to struggle with the loss and the painstaking loneliness, but also with financial hardships and food shortages as a result of the war. Despite these difficulties, Münter's need for artistic reorientation in Scandinavia, under the influence of the cultural environment and the national art movements, led to thematically and stylistically new pictorial creations. The artist found her very own way of artistic expression, with which she kept emancipating herself from the creative years she had shared with Kandinsky in Murnau during the period of the 'Blaue Reiter'. However, she never abandoned the principles she had previously attained, for example the fusion of line and color. Instead she began to develops a very special pictorial language inspired by her Scandinavian environment, once again providing proof of her artistic maturity, but also of an enormous creative drive. A drive that helped her to turn a life crisis into an important period of her career. [CH]

Gabriele Münter's five years in Scandinavia,decisively differed from the previous happy-go-lucky years in Murnau before the First World War, both in private and artistic terms. On the one hand, she finally broke up with her long-time partner Wassily Kandinsky, on the other hand, her work underwent a clear stylistic change and helped her to greater fame and successful solo and group exhibitions in Scandinavia. In the spring of 1918, for example, her largest solo exhibition to date took place in "Den Frie Udstilling" in Copenhagen. The exhibition mainly showed new works created in Scandinavia and attracted more than 600 visitors a day.

In the spring of 1915, the artist had cleared her apartment on Ainmillerstraße in Munich and, after brief stays in Berlin and Copenhagen, finally moved to Stockholm. In politically neutral Sweden, in view of the raging First World War, she hoped for more frequent meetings with Kandinsky, who was living in Moscow at the time. In addition, the sister-in-law of her Berlin gallery owner Herwarth Walden was living in Scandinavia and thus offered Münter a welcome, almost family-like contact. In Stockholm, she managed to gain a foothold surprisingly quickly and established important contacts in the local art scene. "It seems to me that I have not yet seen anything as beautiful, as congenial as Stockholm. Like a better world.", the painter notes on her first evening in Stockholm (quoted from: Karoline Hille, Gabriele Münter. Die Künstlerin mit der Zauberhand, p. 137). She made friends with the painter couple Sigrid Hjertén and Isaac Grünewald and other Swedish painters, and was able to organize several solo and group exhibitions for herself and also for Kandinsky, while her works continued to be shown at the renowned gallery "Der Sturm" in Berlin.

The young painters living and working in Sweden and Denmark, whom Gabriele Münter met during these years, were strongly influenced by Henri Matisse and contemporary French painting. Having completed their training at the Académie Matisse in Paris, many of them took their impressions of French modernism when they returned to Scandinavia, where a so-called decorative expressionism was now gaining ground. It was in these circles that Münter learned the Swedish language, which she soon mastered almost flawlessly in reading and writing, and occupied herself with Swedish culture, among other things on extended trips to northern Sweden.

From the Statuette of the Virgin Mary to the 'Dala Horse'. Gabriele Münter's Passionate Interest in Folk Art

While still in Russia, Kandinsky developed a keen interest in folk art and brought a figure of the Madonna with Child and Crown with Double Cross back to Germany, which is depicted in several Münter paintings. In the years that followed, folk art played an important role in the artistic development of the 'Blauer Reiter', in the works of Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, and also in Gabriele Münter's painting. The artists were impressed by the naivety and originality, the strong colors and the simple, unadorned formal language. In Murnau, Münter and Kandinsky discovered regional reverse glass painting and also began to collect folk sculptures, contemporary nativity figures, crucifixes, statues of the Virgin Mary, votive tablets, as well as back to Germany as well as wooden and clay toys. Although Gabriele Münter certainly had only taken a few individual objects with her to Scandinavia, the work offered here reveals a small radiant light blue wooden toy that, upon closer inspection, turns out to be the ‘Punch and Judy Show’ from Gabriele Münter’s and Wassily Kandinsky's private collection (circa 1900, today in the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich).

Quite as if she also wanted to build a motivic bridge from her creative years in Germany to her artistic production in Scandinavia, the head of a compact, white, painted wooden horse can be seen in our painting in addition to the German wooden toy. It is a traditional Swedish 'Dala horse (Dalahäst)' made of pine wood, which has been made in the province of Dalarna since the 17th century. Today, the horses usually come in red, but in the early 20th century, the horses used to be mostly white, with saddle and bridle painted on them. The horse first appeared in one of Münter's paintings in the spring of 1916 and was also depicted in other paintings, drawings. and one print in the years that followed.

Münter completed the present composition with imaginative ingenuity and compositional finesse with a large green vase with leaves stylized into geometric forms protruding above the arrangement on the right, as well as an object with a colorful bird figure stretched across the height of the picture in the left margin. In the center of the table we see a small blue spherical vase with a bouquet of white flowers and another, shadowed vessel which possibly holds an assortment of different brushes, thus indicating her activity as a painter.

The impression that the objects are placed next to one another incoherently is not confirmed after closer inspection; instead it is a carefully designed, refined composition. There is nothing left of the quite spiritualized Madonna depictions of the Murnau years in her Scandinavian still lifes. The artist began to use the still life to express her more developed and renewed artistic goals: she uses bright, radiant colors, simple, almost geometrical forms, clearly stronger, darker contours, and a particularly curved, decorative line, which can also be found in other still lifes and interior scenes of these years (see illustration).

From the 'Blauer Reiter' to Artistic Independence

After just a single visit to Stockholm, Kandinsky returned to Russia in March 1916, taking a train to Moscow at six in the morning. He kept postponing a second visit until contact between the former couple finally broke off completely - Münter and Kandinsky would never see each other again. In the year the present work was created, only a few months after his visit to Stockholm, Kandinsky married a young Russian woman. Many years later, the artist wrote in a letter to a friend in Sweden: "From 1916 I was no longer a part of his life. After his return from Stockholm at that time, he remained in Russia, kept silent and married a Russian woman. In doing so, he violated the commitment he made in Stockholm, and his principle that our marriage was sacred and that it only needed conscience and not official documents. For me, his unfaithfulness to himself and to me was inconceivable and a heavy blow." (Letter to Carl Palme, March 12, 1949, quoted after: Ex. cat. 1992, p. 69).

In the months that followed, Münter not only had to struggle with the loss and the painstaking loneliness, but also with financial hardships and food shortages as a result of the war. Despite these difficulties, Münter's need for artistic reorientation in Scandinavia, under the influence of the cultural environment and the national art movements, led to thematically and stylistically new pictorial creations. The artist found her very own way of artistic expression, with which she kept emancipating herself from the creative years she had shared with Kandinsky in Murnau during the period of the 'Blaue Reiter'. However, she never abandoned the principles she had previously attained, for example the fusion of line and color. Instead she began to develops a very special pictorial language inspired by her Scandinavian environment, once again providing proof of her artistic maturity, but also of an enormous creative drive. A drive that helped her to turn a life crisis into an important period of her career. [CH]

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.