Video

Frame image

9

Max Beckmann

Holzsäger im Wald, 1931/32.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 600,000 / $ 708,000 Sold:

€ 865,000 / $ 1,020,700 (incl. surcharge)

9

Max Beckmann

Holzsäger im Wald, 1931/32.

Oil on canvas

Estimate:

€ 600,000 / $ 708,000 Sold:

€ 865,000 / $ 1,020,700 (incl. surcharge)

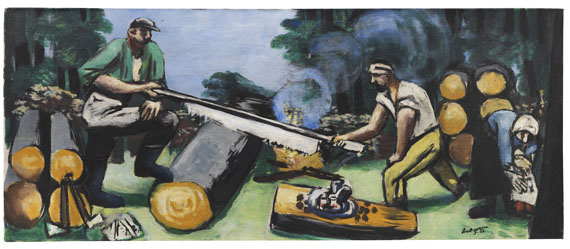

Holzsäger im Wald. 1931/32.

Oil on canvas.

Göpel 349. Lower right signed, dated "32" and inscribed "F" for Frankfurt am Main. 50 x 120 cm (19.6 x 47.2 in).

The work is mentioned on the artist's hand-written list of pictures as follows: "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris - Holzsäger im Wald. - Frankf. a / M - Frau v. Rappop." [AR].

• "Holzsäger im Wald" marks a transition in the artist's creation.

• Up until today, the whereabouts of "Holzsäger im Wald“ were unknwon and this is the first time that it is depicted in colors.

• Käthe von Porada acquired the painting in 1931, as a strong admirer, she played an important role in the artist's life.

• The year the work was made, the Musée du Jeu de Paume acquired the similar work "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller".

• In 1938 part of the historic exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at New Burlington Galleries in London, organized by English, French and German artists and art lovers as a sign of protest against the defamation of German art through the Nazi regime.

PROVENANCE: Studio Max Beckmann

Käthe Anna Rapoport von Porada (1891-1985), Paris/Vence (1931 to at least 1956)

Private collection Southern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Max Beckmann, Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, Berlin, 1932, cat. no. 14 (with the title "Waldarbeiter").

Twentieth Century German Art, New Burlington Galleries, London, July 1938, cat. no. 16 (with the title "Woodcutters" and dated 1933).

Max Beckmann zum Gedächtnis 1884–1950, Haus der Kunst, Munich, June and July 1951, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, Sept. 1951, cat. no. 89.

Max Beckmann 1884–1950, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, November 22, 1955 - January 8, 1956, cat. no. 60 (with the label on the reverse).

Max Beckmann, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, January 14 - February 12, 1956, cat. no. 51.

Max Beckmann, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, March 14 - May 7, 1956, cat. no. 44 (with the label on the reverse of the stretcher)

Max Beckmann, Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart, 1961 (no catalog).

11. Städtische Kunstausstellung. Max Beckmann. Graphik, Ausstellungsräume der Berufsschule, Schwenningen, 1968, cat. no. II.

Max Beckmann. A small loan retrospective of paintings, centred around his visit to London in 1938, Marlborough Fine Arts, London, October 30 - November 29, 1974, cat. no. 14, p. 33 (with illu., with the label on the reverse).

LITERATURE: Anonym, Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, Rezension, in: Der Kunstwanderer 1931/32, p. 200.

Hans Eckstein, Der Maler Max Beckmann, in: Kunst der Nation, Berlin, 1935, vol. 3, no. 4 (on the cover).

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p.15 (with illu. on p. 14).

Beatrice von Bormann, Landschaften des Exils – Max Beckmanns niederländische Jahre 1937-1947, p. 45, in: Kunstmuseum Basel (ed.), Max Beckmann. Die Landschaften, Ostfildern 2011.

Lucy Wasensteiner, Defending 'degenerate' art. London 1938. Mit Kandinsky, Liebermann und Nolde gegen Hitler, London, 2018.

Lucy Wasensteiner, The Twentieth Century German Art Exhibition: Answering Degenerate Art in 1930s London, 2019.

"The 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers slaughtering mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest.“

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p. 15.

Oil on canvas.

Göpel 349. Lower right signed, dated "32" and inscribed "F" for Frankfurt am Main. 50 x 120 cm (19.6 x 47.2 in).

The work is mentioned on the artist's hand-written list of pictures as follows: "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris - Holzsäger im Wald. - Frankf. a / M - Frau v. Rappop." [AR].

• "Holzsäger im Wald" marks a transition in the artist's creation.

• Up until today, the whereabouts of "Holzsäger im Wald“ were unknwon and this is the first time that it is depicted in colors.

• Käthe von Porada acquired the painting in 1931, as a strong admirer, she played an important role in the artist's life.

• The year the work was made, the Musée du Jeu de Paume acquired the similar work "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller".

• In 1938 part of the historic exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at New Burlington Galleries in London, organized by English, French and German artists and art lovers as a sign of protest against the defamation of German art through the Nazi regime.

PROVENANCE: Studio Max Beckmann

Käthe Anna Rapoport von Porada (1891-1985), Paris/Vence (1931 to at least 1956)

Private collection Southern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Max Beckmann, Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, Berlin, 1932, cat. no. 14 (with the title "Waldarbeiter").

Twentieth Century German Art, New Burlington Galleries, London, July 1938, cat. no. 16 (with the title "Woodcutters" and dated 1933).

Max Beckmann zum Gedächtnis 1884–1950, Haus der Kunst, Munich, June and July 1951, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, Sept. 1951, cat. no. 89.

Max Beckmann 1884–1950, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, November 22, 1955 - January 8, 1956, cat. no. 60 (with the label on the reverse).

Max Beckmann, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, January 14 - February 12, 1956, cat. no. 51.

Max Beckmann, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, March 14 - May 7, 1956, cat. no. 44 (with the label on the reverse of the stretcher)

Max Beckmann, Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart, 1961 (no catalog).

11. Städtische Kunstausstellung. Max Beckmann. Graphik, Ausstellungsräume der Berufsschule, Schwenningen, 1968, cat. no. II.

Max Beckmann. A small loan retrospective of paintings, centred around his visit to London in 1938, Marlborough Fine Arts, London, October 30 - November 29, 1974, cat. no. 14, p. 33 (with illu., with the label on the reverse).

LITERATURE: Anonym, Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, Rezension, in: Der Kunstwanderer 1931/32, p. 200.

Hans Eckstein, Der Maler Max Beckmann, in: Kunst der Nation, Berlin, 1935, vol. 3, no. 4 (on the cover).

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p.15 (with illu. on p. 14).

Beatrice von Bormann, Landschaften des Exils – Max Beckmanns niederländische Jahre 1937-1947, p. 45, in: Kunstmuseum Basel (ed.), Max Beckmann. Die Landschaften, Ostfildern 2011.

Lucy Wasensteiner, Defending 'degenerate' art. London 1938. Mit Kandinsky, Liebermann und Nolde gegen Hitler, London, 2018.

Lucy Wasensteiner, The Twentieth Century German Art Exhibition: Answering Degenerate Art in 1930s London, 2019.

"The 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers slaughtering mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest.“

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p. 15.

The art critic, photographer, and acclaimed Beckmann expert Franz Roh characterizes the "Holzsäger im Wald" (Woodcutters in the Forest) in a way that is both striking and bizarre: "The "Holzsäger" from 1931 act like butchers that slaughter mighty trees, in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest." ("Beckmann als Landschafter", in Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, issue 1, October 1951, p. 15) And indeed, the bearded men trim the sturdy trunk resting between them with palpable concentration and great routine. Beckmann observes the strenuous, rhythmic activity on a wide clearing under a blue sky. Piled timber waits to be taken away, branches are burned in a blazing fire, the smoke swirls in the deep green forest. In the far right of the picture a woman wearing a headscarf presumably prepares a snack, while a refreshment awaits the hard-working men on a split log in mid foreground. What fascinated Beckmann so much about this motif, which obviously is quite unusual of his work? Is it the lumberjacks, who quietly pull the saw blade back and forth, not too fast, with just the right amount of pressure, tilting the saw and getting stuck is to be avoided at all costs, as it means a loss of time, it is all about the rhythm. Did the artist witness this spectacle on a walk in Bois de Boulogne in Paris with his Pekingese dogs Majong and Chilly and transferred his discoveries into a painting with a mythical appeal? The answer remains a secret.

From the mid-1920s, Max Beckmann frequently visited the French capital and showed increasing interest in avant-garde painting. He established contacts with critics and gallery owners and tried to pursue his artistic career in France, too. Accordingly, his stays are also reflected in Max Beckmann's paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s. He settled in Paris in 1929 and set up his first studio on Boulevard Brune in the 14th arrondissement. In 1930 he moved to rue des Marronniers in the 16th arrondissement. He decided to spend the months of September to May in Paris and occasionally went back to Frankfurt to spend time with his students at the Städelschule. His efforts to gain recognition in France finally culminated in his first major exhibition at Galerie de la Renaissance from March 16 to April 15, 1931. Earlier assumptions that the "Holzsäger im Wald" were exhibited in the first retrospective at the Paris gallery in the very year they were painted cannot be confirmed, especially because the important show in Paris has been subject of extensive research. (Max Beckmann und Paris, ed. by Tobia Bezzola and Cornelia Homburg, Cologne 1998, p. 189) On the other hand, a painting with a comparable motif and (confusingly) similar title "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller" ("Forest Landscape with Woodcutters") (fig.) from 1927 was on display at Galerie de la Renaissance; it was acquired by the French state for the collection of the Musée des Ecoles Etrangères du Jeu de Paume. For a long time it would be the only purchase made by the country that Beckmann loved so much, not only for its art, but also for its savoir vivre. "The Luxembourg paid only 2,500 Fr. for the 'Holzfäller'. But in view of the advertising you had to do it, of course. - Unfortunately, I have to give Flechtheim a different picture, which I really hate to do. - But for the sake of business, in God's name ", Beckmann wrote to his New York dealer I. B. Neumann on May 25, 1931 (quoted from: Max Beckmann Briefe 1925–1937, vol. II, Munich 1994, p. 200).

Our painting, noted in the picture list with "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris Holzsäger im Wald. Frankf. a / M Frau v. Rappop", found first mention in a publication of Alfred Flechtheim's Berlin gallery for the period between March 5 - 24, 1932. An anonymous writer reviewed the exhibition of Max Beckmann and reported: "There is tension, power and a very own expression of a strong personality. Strongly palpable. First, let's mention a painting that signifies a change in the artist's work, the "Waldarbeiter". Beckmann, merging spirit, imagination, reality into one, shows a simple scene of forest workers sawing logs on a clearing. Beckmann paints the emerald background of the forest, he paints ravishing movement and the rhythm of work, even though not near-natural, he renounces any abstraction, any symbolic representation on the overemphasis of the structure, on any overemphasis at all." (Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, in: Der Kunstwanderer year 1931/32, p. 200). Although enthusiastic, the reviewer deciphers the painting only on the surface, while the spiritual processes that Beckmann wants to tell us about without revealing anything go much deeper into realms of depth psychology. "Beckmann remains", to let Franz Roh have a say again, "with the unbroken volume of things" (Franz Roh, op. cit.).

Käthe Rapoport von Porada

Nevertheless, this undoubtedly unusual painting immediately enthused the equally unusual Käthe Rapoport von Porada. She collected Beckmann's works and also traded them. The "Holzsäger im Wald" was also in her possession, it seems likely that she had acquired them from Flechtheim even before the exhibition.

The fashion journalist Käthe von Porada, née Magnus (Berlin 1891 - Antibes 1985), grew up in Berlin, and came into contact with theater- and literary circles, such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Gerhart Hauptmann and Arthur Schnitzler as a young woman. In 1911 she married the wealthy Viennese landowner Dr. Alfred Rapoport Edler von Porada and lived with him in Vienna. After they separated, she lived in both Vienna and Frankfurt am Main, where in 1924 she would eventually find an apartment on Untermainkai 21, just opposite from Beckmann's first place in Frankfurt with the Battenbergs, on the other side of the river Main. She wrote fashion reports for the Frankfurter Zeitung and gained access to the circle around the editor Heinrich Simons, which included luminaries like Thomas Mann and Max Beckmann. There are different stories about the first encounter between Beckmann and Porada. According to Porada's memoirs, she was present when Beckmann met his future wife Mathilde von Kaulbach in Vienna at the home of the Motesiczky family. (Marie-Louise von Motesiczky became Beckmann's master student in the mid 1920s.) Käthe von Porada would take on an important role in the artist's life. In 1928 she moved to Paris as a fashion journalist for the Ullstein publishing house and the Frankfurter Zeitung. For Beckmann, who regularly stayed in Paris at that point, she was very helpful: she found an apartment and a studio for his lengthy stays, helped him organize his daily life, and in 1930 introduced him to the influential poet and writer Philippe Soupault, who wrote an essay about Max Beckmann on the occasion of the exhibition at the Galerie de la Renaissance. In times of persecution and exile, von Porada was a reliable, loyal friend to Beckmann and helped him and his wife to prepare their move into exile in Amsterdam in 1937. Together with the American Stephan Lackner, collector, author and friend of the artist, von Porada organized an extensive exhibition of Beckmann's works in Bern in 1938, which was subsequently shown in Winterthur, Zurich and Basel. She was in contact with publishers and art dealers, among them I. B. Neumann in Berlin and Günter Franke in Munich. When a planned Beckmann show at Galerie Alfred Poyet in Paris was canceled for political reasons shortly before its opening in 1939, Porada decided to show his watercolors in her private apartment on Rue de la Pompe. At the outbreak of World War II, she found shelter with friends in Monte Carlo, where she remained until 1946. After a brief return to Paris, she settled in Vence near Nice until her death.

And Käthe von Porada was also a lender for the exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at the Burlington in London (fig.). With this exhibition, English, French and German artists and art lovers protested against the defamation of German art by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937. Influential personalities at the time, such as Herbert Read, writer, philosopher and editor of the Burlington Magazine, the Zurich-born painter and art dealer Irmgard Burchard and the writer, collector and art critic Paul Westheim, who had already emigrated to Paris at that time, were in charge of the exhibition of around 300 works from July 7 to August 27, 1938. About half of the exhibits came from German emigrants and artists defamed as "degenerate" by the National Socialists. In order to avoid putting the artists at risk, mainly loans from museums and private collections were shown. On July 21, 1938, Max Beckmann delivered his famous lecture "Meine Theorie der Malerei". Of the six works by the artist two, namely the "Holzsäger im Wald" and "Hafen von Genua" from 1927 (fig.), were contributed by Käthe von Porada, while three works, including the triptych "Versuchung" came from the collection of Stefan Lackner (fig.). [MvL]"The 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers slaughtering mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest."

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p. 15.

The art critic, photographer, and acclaimed Beckmann expert Franz Roh characterizes the "Holzsäger im Wald" (Woodcutters in the Forest) in a way that is both striking and bizarre: "The "Holzsäger" from 1931 act like butchers that slaughter mighty trees, in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest." ("Beckmann als Landschafter", in Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, issue 1, October 1951, p. 15) And indeed, the bearded men trim the sturdy trunk resting between them with palpable concentration and great routine. Beckmann observes the strenuous, rhythmic activity on a wide clearing under a blue sky. Piled timber waits to be taken away, branches are burned in a blazing fire, the smoke swirls in the deep green forest. In the far right of the picture a woman wearing a headscarf presumably prepares a snack, while a refreshment awaits the hard-working men on a split log in mid foreground. What fascinated Beckmann so much about this motif, which obviously is quite unusual of his work? Is it the lumberjacks, who quietly pull the saw blade back and forth, not too fast, with just the right amount of pressure, tilting the saw and getting stuck is to be avoided at all costs, as it means a loss of time, it is all about the rhythm. Did the artist witness this spectacle on a walk in Bois de Boulogne in Paris with his Pekingese dogs Majong and Chilly and transferred his discoveries into a painting with a mythical appeal? The answer remains a secret.

From the mid-1920s, Max Beckmann frequently visited the French capital and showed increasing interest in avant-garde painting. He established contacts with critics and gallery owners and tried to pursue his artistic career in France, too. Accordingly, his stays are also reflected in Max Beckmann's paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s. He settled in Paris in 1929 and set up his first studio on Boulevard Brune in the 14th arrondissement. In 1930 he moved to rue des Marronniers in the 16th arrondissement. He decided to spend the months of September to May in Paris and occasionally went back to Frankfurt to spend time with his students at the Städelschule. His efforts to gain recognition in France finally culminated in his first major exhibition at Galerie de la Renaissance from March 16 to April 15, 1931. Earlier assumptions that the "Holzsäger im Wald" were exhibited in the first retrospective at the Paris gallery in the very year they were painted cannot be confirmed, especially because the important show in Paris has been subject of extensive research. (Max Beckmann und Paris, ed. by Tobia Bezzola and Cornelia Homburg, Cologne 1998, p. 189) On the other hand, a painting with a comparable motif and (confusingly) similar title "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller" ("Forest Landscape with Woodcutters") (fig.) from 1927 was on display at Galerie de la Renaissance; it was acquired by the French state for the collection of the Musée des Ecoles Etrangères du Jeu de Paume. For a long time it would be the only purchase made by the country that Beckmann loved so much, not only for its art, but also for its savoir vivre. "The Luxembourg paid only 2,500 Fr. for the 'Holzfäller'. But in view of the advertising you had to do it, of course. - Unfortunately, I have to give Flechtheim a different picture, which I really hate to do. - But for the sake of business, in God's name ", Beckmann wrote to his New York dealer I. B. Neumann on May 25, 1931 (quoted from: Max Beckmann Briefe 1925–1937, vol. II, Munich 1994, p. 200).

Our painting, noted in the picture list with "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris Holzsäger im Wald. Frankf. a / M Frau v. Rappop", found first mention in a publication of Alfred Flechtheim's Berlin gallery for the period between March 5 - 24, 1932. An anonymous writer reviewed the exhibition of Max Beckmann and reported: "There is tension, power and a very own expression of a strong personality. Strongly palpable. First, let's mention a painting that signifies a change in the artist's work, the "Waldarbeiter". Beckmann, merging spirit, imagination, reality into one, shows a simple scene of forest workers sawing logs on a clearing. Beckmann paints the emerald background of the forest, he paints ravishing movement and the rhythm of work, even though not near-natural, he renounces any abstraction, any symbolic representation on the overemphasis of the structure, on any overemphasis at all." (Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, in: Der Kunstwanderer year 1931/32, p. 200). Although enthusiastic, the reviewer deciphers the painting only on the surface, while the spiritual processes that Beckmann wants to tell us about without revealing anything go much deeper into realms of depth psychology. "Beckmann remains", to let Franz Roh have a say again, "with the unbroken volume of things" (Franz Roh, op. Cit.).

The "Holzsäger". A cultural-political perspective

The political situation in Germany, which had been festering for years, changed dramatically as of 1930, and along with it the cultural situation. In August 1927, Heinrich Himmler founded the "National Socialist Society for German Culture" together with a group of chief NSDAP ideologues around Alfred Rosenberg (author of "The Myth of the 20th Century") and Gregor Strasser, which was renamed "Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur" (Militant League for German Culture) in 1928. In the 1920s, the National Socialist movement sought access to middle-class circles through art. The ‘Kampfbund’ attracted all sorts of nationalist and antisemitic groups united by the idea of a common enemy. On September 15, 1930, a troubled Beckmann reported to his wife Mathilde about the activities on the Frankfurt streets: "[...] the people out there already know of Germany's fate." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, p. 172) The Reichstag elections the day before, September 14, were a political landslide: The NSDAP won 107 of the 575 Reichstag seats and became the second largest parliamentary group. Beckmann already had a vague idea of what it would mean for him as an artist if the National Socialists became the strongest force. On October 23, he wrote to his art dealer Günther Franke: "Don't forget to tell the Nazis I am a German painter, if you have the opportunity. On Wednesday the ‘Völkische Beobachter’ already attacked me. Do not forget that. – It might be important one day." (Max Beckmann, letters 1925-1937, p. 178) What had happened?

While Beckmann spent the summer of 1930 in Paris, two NSDAP members were part of the newly elected Thuringian state government. What the artists would have to expect in the event of a takeover became clear when the National Socialists had Oskar Schlemmer’s staircase painting at the Bauhaus building painted over in a cloak-and-dagger operation. In early November 1930, they removed works by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Molzahn and Walter Dexel from the "Department for New Art" in the Weimar Art Collections. The National Socialist iconoclasm began. At the same time, Max Beckmann, who taught in Frankfurt and lived in Paris, showed the large-format painting "Der Strand" (The Beach, 1927) at the 17th Venice Biennale in 1930, for which the conservative newspaper Corriere della Sera criticized him, which, in return, attracted the attention of the National Socialists. The ‘Völkischer Beobachter’ reacted with the article "Das Delirium der Häßlichkeit“ (The Delirium of Ugliness), which regarded Max Beckmann's "Lido" picture as particularly "lewd" and also threatened Georg Swarzenski, long-time director of the Städelsche Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt am Main and the lender of the painting: "One should remember it. […] Delirium of ugliness? Yes! Away with this phantom of internationalism! Come on you men with an awareness of the German species! The time has come." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, commentary, pp. 392f.) Max Beckmann, who had been increasingly exposed to hostilities since the Venice Biennale, wrote to Reinhard Piper on February 15, 1932: "I am trying to work hard to get over the untalented insanity of the time. - In the long run, one becomes so ridiculously indifferent to all this political gangsterism and feels happiest on the island of the own soul." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925-1937, p. 212)

Max Beckmann was by no means intimidated by the political scenario and the defamation. His goal was to gain a foothold in France, to become established next to Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger, even if critics branded him as an awkward and deeply German painter. He, who was committed to the fathers of modernism such as Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh. and at the same time reflected on Old Master art, was aware thereof; and it did neither occurred to him to seek Matisse’s lightness of motif and color, nor to give his painting the distorted quality of a Picasso or to imitate Léger's machine art. With the scene of the lumberjacks in the forest, Beckmann painted a deeply German motif in France. The forest had become a highly symbolically charged motif, the latest since Caspar David Friedrich at the beginning of the 19th century, and was misused by Alfred Rosenberg's projections of a blood-and-soil mythology. The established image of a "German forest" served to justify cultural politics. The research work "Wald und Baum" (Forest and Tree) and the project "Wiederbewaldung des Ostens" (Reforestation of the East) eventually led to the film project "Der ewige Wald" (The Eternal Forest, 1936) and became a subject that the National Socialist’s heavily exploited for their cultural politics. (<a href="https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10571/pdf/Linse_1993_Der_Film_Ewiger_Wald.pdf" target="_blank">https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10571/pdf/Linse_1993_Der_Film_Ewiger_Wald.pdf</a>)

However, the painting "Holzsäger im Wald" was created much earlier, in Paris in 1931, and Beckmann signed the work in Frankfurt in 1932 before Flechtheim exhibited it in Berlin in March. The "Holzsäger" are undoubtedly unusual in Beckmann's oeuvre of the early 1930s, so that perhaps the rowdy SA actions in the cities may be the background here; while the quote from Franz Roh about the motif: "By the way, the 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers who slaughter mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest." perhaps has a second, more subliminal meaning. Beckmann may have consciously borrowed from National Socialist ideology and rhetoric, in order to unmask the the contradictions of the stereotypes of Nazi propaganda. Beckmann, who has the forest workers cut the trees for transportation, implicitly alludes to the NSDAP’s cultural politics: remove, smash, clear. In this sense, the sawyers also dismantle the 'German forest', the Nazi-abused identification symbol.

Parallel to the creation of the painting, Beckmann was also concerned with the upcoming extension of his contract as a teacher at the Städelschule. With effect from October 1, 1930, it was "extended under the previous conditions. [...] his affiliation with the 'Kunstgewerbeschule' means a greater gain for the school. Max Beckmann's art was showcased in exhibitions in Basel and Zurich later this year, and will be on display in Paris and America next year. It is already represented in almost all important museums." (Quoted from: ex. cat. Max Beckmann. Frankfurt 1915–1933, Frankfurt am Main 1983, p. 333) A year later a dispute arose between Fritz Wichert, former director of the Mannheim Kunsthalle and director of the Städelschule since 1923, and Beckmann. Wichert had hired the artist in 1925, but he began to accuse him of a lack of presence in Frankfurt. Beckmann wanted to protect his freedom and resigned on October 26, 1931. However, the Frankfurt mayor Ludwig Landmann, as well as Max Michel, head of the Department of Cultural Affairs and the director of the Städel, Georg Swarzenski, intervened; Beckmann remained professor in Frankfurt. For Beckmann, however, this wave of success was soon disrupted. It is true that Hildebrand Gurlitt in Hamburg and Herbert Kunze in Erfurt were planning another exhibition of Beckmann's works for the spring of 1933, and Ludwig Justi, director of the Nationalgalerie, set up a separate room for ten Beckmann paintings at the Berlin Kronprinzenpalais, which, as part of a general rearrangement of the works, was presented to the public on February 15. In early July, both the Berlin presentation and the Erfurt exhibition were canceled by the order of the National Socialists.

In the midst of extensive planning and an emotional rollercoaster, Beckmann began to work on his first triptych in Frankfurt in May 1932, in which he combined various symbols of existence. After its completion in Berlin in 1935, the individual panels were initially given innocuous titles such as "The Castle", "Homecoming", "The Stairs", while Beckmann only later came up with the highly visionary title "Departure". "The two spheres of enslavement of man and the dawn of freedom are irreconcilably contrasted. During the Nazi era, this work also had to be seen as an allegory of the political situation in Germany," said Stephan von Wiese, co-editor of the Beckmann letters, in his introduction . (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, p. 12) In a conversation with Lilly von Schnitzler, Beckmann collector and patron, in February 1937, Beckmann explained the subtle content of the three panels: “What you see on the right and left is life . Life is torture, all kinds of pain - physical and mental pain. On the right panel you see yourself trying to find your way in the dark. You light up the room and staircase with a miserable dim light, as part of yourself, you drag along the corpses of your memories, your misdeeds and failures, the murders everyone commits at some point in their lives. You can never free yourself from your past, you have to carry this corpse while life beats the drum." ["And the center panel?" Frau von Schnitzler asked.] "King and queen, husband and wife, taken across the river by an unknown ferryman wearing a mask, he's the mysterious figure that takes us to a mysterious land. ... King and queen have freed themselves from the torments of existence - they have overcome them. The queen carries the greatest treasure - freedom - as a child on her lap. Freedom is what matters – it is the departure, the new beginning." (Max Beckmann. Die Realität der Träume in den Bildern, Leipzig 1987, p. 129) Beckmann's collector and friend Stephan Lackner and his New York gallerist Curt Valentin acquired the triptych "Departure" in 1937 and gave it to the Museum of Modern Art in an exchange in 1942.

It is obvious that Max Beckmann was well aware of the intentions the new rulers had. In anticipation, he rented an apartment in Berlin in January 1933. After Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Beckmann lost his post at the at the ‘Municipal School of Applied Arts’ in Frankfurt in March 1933. After around 18 years, Beckmann and his wife Mathilde left Frankfurt and moved to Berlin. The Beckmanns occasionally left the big city and its political tensions and visited Mathilde Beckmann’s sister Hedda in Holland, where she lived with the Dutch organist Valentijn Schoonderbeek, or they traveled to Ohlstadt, south of Murnau, to visit family.

On the occasion of the opening of the "Haus der deutschen Kunst" (House of German Art) on July 18, 1937, Hitler delivered his programmatic speech in which he declared modern art "degenerate". Concomitant threats prompted the Beckmanns to leave Germany and to emigrate to Holland, where they settled in Amsterdam. The confiscation of his works in museums in July and the defamation in the exhibition "Degenerate Art" in Munich undoubtedly supported his decision to live in exile. Despite the complicated everyday life, the following ten years in Amsterdam were tremendously productive. A rebellion against the forces of degradation, the unspiritual, the inhumane. It is not only his Amsterdam works that directly reflect the tremendous perfidy with which the National Socialists had been terrorizing their own country and also its neighbors for years. Between quotations from literary dramas and interpretations of ancient mythology, Beckmann hides his messages in everyday painting and describes the confusing distortions of the world. Even in his early works, Max Beckmann felt he had to work up the horrors of world history and depicted the events on vivid theater stages in his pictures, such as the industrious work of the sawyers in the present work. The loss of virtues made Beckmann a cynical interpreter of the events after World War I. Beckmann never gave up addressing current events, on the contrary, even when his new Amsterdam home was under the control of German troops, he noted in his diary on September 22, 1940: "If you consider all of this – the entire war or life as nothing but a scene in the theater of infinity, it is much easier to bear." (Max Beckmann, Tagebücher, 1940–1950, Munich 1955, September 22, 1940)

Käthe Rapoport von Porada

Nevertheless, this undoubtedly unusual painting immediately enthused the equally unusual Käthe Rapoport von Porada. She collected Beckmann's works and also traded them. The "Holzsäger im Wald" was also in her possession, it seems likely that she had acquired them from Flechtheim even before the exhibition.

The fashion journalist Käthe von Porada, née Magnus (Berlin 1891 - Antibes 1985), grew up in Berlin, and came into contact with theater- and literary circles, such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Gerhart Hauptmann and Arthur Schnitzler as a young woman. In 1911 she married the wealthy Viennese landowner Dr. Alfred Rapoport Edler von Porada and lived with him in Vienna. After they separated, she lived in both Vienna and Frankfurt am Main, where in 1924 she would eventually find an apartment on Untermainkai 21, just opposite from Beckmann's first place in Frankfurt with the Battenbergs, on the other side of the river Main. She wrote fashion reports for the Frankfurter Zeitung and gained access to the circle around the editor Heinrich Simons, which included luminaries like Thomas Mann and Max Beckmann. There are different stories about the first encounter between Beckmann and Porada. According to Porada's memoirs, she was present when Beckmann met his future wife Mathilde von Kaulbach in Vienna at the home of the Motesiczky family. (Marie-Louise von Motesiczky became Beckmann's master student in the mid 1920s.) Käthe von Porada would take on an important role in the artist's life. In 1928 she moved to Paris as a fashion journalist for the Ullstein publishing house and the Frankfurter Zeitung. For Beckmann, who regularly stayed in Paris at that point, she was very helpful: she found an apartment and a studio for his lengthy stays, helped him organize his daily life, and in 1930 introduced him to the influential poet and writer Philippe Soupault, who wrote an essay about Max Beckmann on the occasion of the exhibition at the Galerie de la Renaissance. In times of persecution and exile, von Porada was a reliable, loyal friend to Beckmann and helped him and his wife to prepare their move into exile in Amsterdam in 1937. Together with the American Stephan Lackner, collector, author and friend of the artist, von Porada organized an extensive exhibition of Beckmann's works in Bern in 1938, which was subsequently shown in Winterthur, Zurich and Basel. She was in contact with publishers and art dealers, among them I. B. Neumann in Berlin and Günter Franke in Munich. When a planned Beckmann show at Galerie Alfred Poyet in Paris was canceled for political reasons shortly before its opening in 1939, Porada decided to show his watercolors in her private apartment on Rue de la Pompe. At the outbreak of World War II, she found shelter with friends in Monte Carlo, where she remained until 1946. After a brief return to Paris, she settled in Vence near Nice until her death.

And Käthe von Porada was also a lender for the exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at the Burlington in London (fig.). With this exhibition, English, French and German artists and art lovers protested against the defamation of German art by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937. Influential personalities at the time, such as Herbert Read, writer, philosopher and editor of the Burlington Magazine, the Zurich-born painter and art dealer Irmgard Burchard and the writer, collector and art critic Paul Westheim, who had already emigrated to Paris at that time, were in charge of the exhibition of around 300 works from July 7 to August 27, 1938. About half of the exhibits came from German emigrants and artists defamed as "degenerate" by the National Socialists. In order to avoid putting the artists at risk, mainly loans from museums and private collections were shown. On July 21, 1938, Max Beckmann delivered his famous lecture "Meine Theorie der Malerei". Of the six works by the artist two, namely the "Holzsäger im Wald" and "Hafen von Genua" from 1927 (fig.), were contributed by Käthe von Porada, while three works, including the triptych "Versuchung" came from the collection of Stefan Lackner (fig.). [MvL]

From the mid-1920s, Max Beckmann frequently visited the French capital and showed increasing interest in avant-garde painting. He established contacts with critics and gallery owners and tried to pursue his artistic career in France, too. Accordingly, his stays are also reflected in Max Beckmann's paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s. He settled in Paris in 1929 and set up his first studio on Boulevard Brune in the 14th arrondissement. In 1930 he moved to rue des Marronniers in the 16th arrondissement. He decided to spend the months of September to May in Paris and occasionally went back to Frankfurt to spend time with his students at the Städelschule. His efforts to gain recognition in France finally culminated in his first major exhibition at Galerie de la Renaissance from March 16 to April 15, 1931. Earlier assumptions that the "Holzsäger im Wald" were exhibited in the first retrospective at the Paris gallery in the very year they were painted cannot be confirmed, especially because the important show in Paris has been subject of extensive research. (Max Beckmann und Paris, ed. by Tobia Bezzola and Cornelia Homburg, Cologne 1998, p. 189) On the other hand, a painting with a comparable motif and (confusingly) similar title "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller" ("Forest Landscape with Woodcutters") (fig.) from 1927 was on display at Galerie de la Renaissance; it was acquired by the French state for the collection of the Musée des Ecoles Etrangères du Jeu de Paume. For a long time it would be the only purchase made by the country that Beckmann loved so much, not only for its art, but also for its savoir vivre. "The Luxembourg paid only 2,500 Fr. for the 'Holzfäller'. But in view of the advertising you had to do it, of course. - Unfortunately, I have to give Flechtheim a different picture, which I really hate to do. - But for the sake of business, in God's name ", Beckmann wrote to his New York dealer I. B. Neumann on May 25, 1931 (quoted from: Max Beckmann Briefe 1925–1937, vol. II, Munich 1994, p. 200).

Our painting, noted in the picture list with "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris Holzsäger im Wald. Frankf. a / M Frau v. Rappop", found first mention in a publication of Alfred Flechtheim's Berlin gallery for the period between March 5 - 24, 1932. An anonymous writer reviewed the exhibition of Max Beckmann and reported: "There is tension, power and a very own expression of a strong personality. Strongly palpable. First, let's mention a painting that signifies a change in the artist's work, the "Waldarbeiter". Beckmann, merging spirit, imagination, reality into one, shows a simple scene of forest workers sawing logs on a clearing. Beckmann paints the emerald background of the forest, he paints ravishing movement and the rhythm of work, even though not near-natural, he renounces any abstraction, any symbolic representation on the overemphasis of the structure, on any overemphasis at all." (Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, in: Der Kunstwanderer year 1931/32, p. 200). Although enthusiastic, the reviewer deciphers the painting only on the surface, while the spiritual processes that Beckmann wants to tell us about without revealing anything go much deeper into realms of depth psychology. "Beckmann remains", to let Franz Roh have a say again, "with the unbroken volume of things" (Franz Roh, op. cit.).

Käthe Rapoport von Porada

Nevertheless, this undoubtedly unusual painting immediately enthused the equally unusual Käthe Rapoport von Porada. She collected Beckmann's works and also traded them. The "Holzsäger im Wald" was also in her possession, it seems likely that she had acquired them from Flechtheim even before the exhibition.

The fashion journalist Käthe von Porada, née Magnus (Berlin 1891 - Antibes 1985), grew up in Berlin, and came into contact with theater- and literary circles, such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Gerhart Hauptmann and Arthur Schnitzler as a young woman. In 1911 she married the wealthy Viennese landowner Dr. Alfred Rapoport Edler von Porada and lived with him in Vienna. After they separated, she lived in both Vienna and Frankfurt am Main, where in 1924 she would eventually find an apartment on Untermainkai 21, just opposite from Beckmann's first place in Frankfurt with the Battenbergs, on the other side of the river Main. She wrote fashion reports for the Frankfurter Zeitung and gained access to the circle around the editor Heinrich Simons, which included luminaries like Thomas Mann and Max Beckmann. There are different stories about the first encounter between Beckmann and Porada. According to Porada's memoirs, she was present when Beckmann met his future wife Mathilde von Kaulbach in Vienna at the home of the Motesiczky family. (Marie-Louise von Motesiczky became Beckmann's master student in the mid 1920s.) Käthe von Porada would take on an important role in the artist's life. In 1928 she moved to Paris as a fashion journalist for the Ullstein publishing house and the Frankfurter Zeitung. For Beckmann, who regularly stayed in Paris at that point, she was very helpful: she found an apartment and a studio for his lengthy stays, helped him organize his daily life, and in 1930 introduced him to the influential poet and writer Philippe Soupault, who wrote an essay about Max Beckmann on the occasion of the exhibition at the Galerie de la Renaissance. In times of persecution and exile, von Porada was a reliable, loyal friend to Beckmann and helped him and his wife to prepare their move into exile in Amsterdam in 1937. Together with the American Stephan Lackner, collector, author and friend of the artist, von Porada organized an extensive exhibition of Beckmann's works in Bern in 1938, which was subsequently shown in Winterthur, Zurich and Basel. She was in contact with publishers and art dealers, among them I. B. Neumann in Berlin and Günter Franke in Munich. When a planned Beckmann show at Galerie Alfred Poyet in Paris was canceled for political reasons shortly before its opening in 1939, Porada decided to show his watercolors in her private apartment on Rue de la Pompe. At the outbreak of World War II, she found shelter with friends in Monte Carlo, where she remained until 1946. After a brief return to Paris, she settled in Vence near Nice until her death.

And Käthe von Porada was also a lender for the exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at the Burlington in London (fig.). With this exhibition, English, French and German artists and art lovers protested against the defamation of German art by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937. Influential personalities at the time, such as Herbert Read, writer, philosopher and editor of the Burlington Magazine, the Zurich-born painter and art dealer Irmgard Burchard and the writer, collector and art critic Paul Westheim, who had already emigrated to Paris at that time, were in charge of the exhibition of around 300 works from July 7 to August 27, 1938. About half of the exhibits came from German emigrants and artists defamed as "degenerate" by the National Socialists. In order to avoid putting the artists at risk, mainly loans from museums and private collections were shown. On July 21, 1938, Max Beckmann delivered his famous lecture "Meine Theorie der Malerei". Of the six works by the artist two, namely the "Holzsäger im Wald" and "Hafen von Genua" from 1927 (fig.), were contributed by Käthe von Porada, while three works, including the triptych "Versuchung" came from the collection of Stefan Lackner (fig.). [MvL]"The 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers slaughtering mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest."

Franz Roh, Beckmann als Landschafter, in: Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, 50.1951, issue 1, p. 15.

The art critic, photographer, and acclaimed Beckmann expert Franz Roh characterizes the "Holzsäger im Wald" (Woodcutters in the Forest) in a way that is both striking and bizarre: "The "Holzsäger" from 1931 act like butchers that slaughter mighty trees, in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest." ("Beckmann als Landschafter", in Die Kunst und das schöne Heim, issue 1, October 1951, p. 15) And indeed, the bearded men trim the sturdy trunk resting between them with palpable concentration and great routine. Beckmann observes the strenuous, rhythmic activity on a wide clearing under a blue sky. Piled timber waits to be taken away, branches are burned in a blazing fire, the smoke swirls in the deep green forest. In the far right of the picture a woman wearing a headscarf presumably prepares a snack, while a refreshment awaits the hard-working men on a split log in mid foreground. What fascinated Beckmann so much about this motif, which obviously is quite unusual of his work? Is it the lumberjacks, who quietly pull the saw blade back and forth, not too fast, with just the right amount of pressure, tilting the saw and getting stuck is to be avoided at all costs, as it means a loss of time, it is all about the rhythm. Did the artist witness this spectacle on a walk in Bois de Boulogne in Paris with his Pekingese dogs Majong and Chilly and transferred his discoveries into a painting with a mythical appeal? The answer remains a secret.

From the mid-1920s, Max Beckmann frequently visited the French capital and showed increasing interest in avant-garde painting. He established contacts with critics and gallery owners and tried to pursue his artistic career in France, too. Accordingly, his stays are also reflected in Max Beckmann's paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s. He settled in Paris in 1929 and set up his first studio on Boulevard Brune in the 14th arrondissement. In 1930 he moved to rue des Marronniers in the 16th arrondissement. He decided to spend the months of September to May in Paris and occasionally went back to Frankfurt to spend time with his students at the Städelschule. His efforts to gain recognition in France finally culminated in his first major exhibition at Galerie de la Renaissance from March 16 to April 15, 1931. Earlier assumptions that the "Holzsäger im Wald" were exhibited in the first retrospective at the Paris gallery in the very year they were painted cannot be confirmed, especially because the important show in Paris has been subject of extensive research. (Max Beckmann und Paris, ed. by Tobia Bezzola and Cornelia Homburg, Cologne 1998, p. 189) On the other hand, a painting with a comparable motif and (confusingly) similar title "Waldlandschaft mit Holzfäller" ("Forest Landscape with Woodcutters") (fig.) from 1927 was on display at Galerie de la Renaissance; it was acquired by the French state for the collection of the Musée des Ecoles Etrangères du Jeu de Paume. For a long time it would be the only purchase made by the country that Beckmann loved so much, not only for its art, but also for its savoir vivre. "The Luxembourg paid only 2,500 Fr. for the 'Holzfäller'. But in view of the advertising you had to do it, of course. - Unfortunately, I have to give Flechtheim a different picture, which I really hate to do. - But for the sake of business, in God's name ", Beckmann wrote to his New York dealer I. B. Neumann on May 25, 1931 (quoted from: Max Beckmann Briefe 1925–1937, vol. II, Munich 1994, p. 200).

Our painting, noted in the picture list with "1931 Frankfurt u. Paris Holzsäger im Wald. Frankf. a / M Frau v. Rappop", found first mention in a publication of Alfred Flechtheim's Berlin gallery for the period between March 5 - 24, 1932. An anonymous writer reviewed the exhibition of Max Beckmann and reported: "There is tension, power and a very own expression of a strong personality. Strongly palpable. First, let's mention a painting that signifies a change in the artist's work, the "Waldarbeiter". Beckmann, merging spirit, imagination, reality into one, shows a simple scene of forest workers sawing logs on a clearing. Beckmann paints the emerald background of the forest, he paints ravishing movement and the rhythm of work, even though not near-natural, he renounces any abstraction, any symbolic representation on the overemphasis of the structure, on any overemphasis at all." (Kunstausstellungen in Berlin, in: Der Kunstwanderer year 1931/32, p. 200). Although enthusiastic, the reviewer deciphers the painting only on the surface, while the spiritual processes that Beckmann wants to tell us about without revealing anything go much deeper into realms of depth psychology. "Beckmann remains", to let Franz Roh have a say again, "with the unbroken volume of things" (Franz Roh, op. Cit.).

The "Holzsäger". A cultural-political perspective

The political situation in Germany, which had been festering for years, changed dramatically as of 1930, and along with it the cultural situation. In August 1927, Heinrich Himmler founded the "National Socialist Society for German Culture" together with a group of chief NSDAP ideologues around Alfred Rosenberg (author of "The Myth of the 20th Century") and Gregor Strasser, which was renamed "Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur" (Militant League for German Culture) in 1928. In the 1920s, the National Socialist movement sought access to middle-class circles through art. The ‘Kampfbund’ attracted all sorts of nationalist and antisemitic groups united by the idea of a common enemy. On September 15, 1930, a troubled Beckmann reported to his wife Mathilde about the activities on the Frankfurt streets: "[...] the people out there already know of Germany's fate." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, p. 172) The Reichstag elections the day before, September 14, were a political landslide: The NSDAP won 107 of the 575 Reichstag seats and became the second largest parliamentary group. Beckmann already had a vague idea of what it would mean for him as an artist if the National Socialists became the strongest force. On October 23, he wrote to his art dealer Günther Franke: "Don't forget to tell the Nazis I am a German painter, if you have the opportunity. On Wednesday the ‘Völkische Beobachter’ already attacked me. Do not forget that. – It might be important one day." (Max Beckmann, letters 1925-1937, p. 178) What had happened?

While Beckmann spent the summer of 1930 in Paris, two NSDAP members were part of the newly elected Thuringian state government. What the artists would have to expect in the event of a takeover became clear when the National Socialists had Oskar Schlemmer’s staircase painting at the Bauhaus building painted over in a cloak-and-dagger operation. In early November 1930, they removed works by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Molzahn and Walter Dexel from the "Department for New Art" in the Weimar Art Collections. The National Socialist iconoclasm began. At the same time, Max Beckmann, who taught in Frankfurt and lived in Paris, showed the large-format painting "Der Strand" (The Beach, 1927) at the 17th Venice Biennale in 1930, for which the conservative newspaper Corriere della Sera criticized him, which, in return, attracted the attention of the National Socialists. The ‘Völkischer Beobachter’ reacted with the article "Das Delirium der Häßlichkeit“ (The Delirium of Ugliness), which regarded Max Beckmann's "Lido" picture as particularly "lewd" and also threatened Georg Swarzenski, long-time director of the Städelsche Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt am Main and the lender of the painting: "One should remember it. […] Delirium of ugliness? Yes! Away with this phantom of internationalism! Come on you men with an awareness of the German species! The time has come." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, commentary, pp. 392f.) Max Beckmann, who had been increasingly exposed to hostilities since the Venice Biennale, wrote to Reinhard Piper on February 15, 1932: "I am trying to work hard to get over the untalented insanity of the time. - In the long run, one becomes so ridiculously indifferent to all this political gangsterism and feels happiest on the island of the own soul." (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925-1937, p. 212)

Max Beckmann was by no means intimidated by the political scenario and the defamation. His goal was to gain a foothold in France, to become established next to Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger, even if critics branded him as an awkward and deeply German painter. He, who was committed to the fathers of modernism such as Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh. and at the same time reflected on Old Master art, was aware thereof; and it did neither occurred to him to seek Matisse’s lightness of motif and color, nor to give his painting the distorted quality of a Picasso or to imitate Léger's machine art. With the scene of the lumberjacks in the forest, Beckmann painted a deeply German motif in France. The forest had become a highly symbolically charged motif, the latest since Caspar David Friedrich at the beginning of the 19th century, and was misused by Alfred Rosenberg's projections of a blood-and-soil mythology. The established image of a "German forest" served to justify cultural politics. The research work "Wald und Baum" (Forest and Tree) and the project "Wiederbewaldung des Ostens" (Reforestation of the East) eventually led to the film project "Der ewige Wald" (The Eternal Forest, 1936) and became a subject that the National Socialist’s heavily exploited for their cultural politics. (<a href="https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10571/pdf/Linse_1993_Der_Film_Ewiger_Wald.pdf" target="_blank">https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10571/pdf/Linse_1993_Der_Film_Ewiger_Wald.pdf</a>)

However, the painting "Holzsäger im Wald" was created much earlier, in Paris in 1931, and Beckmann signed the work in Frankfurt in 1932 before Flechtheim exhibited it in Berlin in March. The "Holzsäger" are undoubtedly unusual in Beckmann's oeuvre of the early 1930s, so that perhaps the rowdy SA actions in the cities may be the background here; while the quote from Franz Roh about the motif: "By the way, the 'Holzsäger' from 1931 act like butchers who slaughter mighty trees in the middle of a pleasant dark green forest." perhaps has a second, more subliminal meaning. Beckmann may have consciously borrowed from National Socialist ideology and rhetoric, in order to unmask the the contradictions of the stereotypes of Nazi propaganda. Beckmann, who has the forest workers cut the trees for transportation, implicitly alludes to the NSDAP’s cultural politics: remove, smash, clear. In this sense, the sawyers also dismantle the 'German forest', the Nazi-abused identification symbol.

Parallel to the creation of the painting, Beckmann was also concerned with the upcoming extension of his contract as a teacher at the Städelschule. With effect from October 1, 1930, it was "extended under the previous conditions. [...] his affiliation with the 'Kunstgewerbeschule' means a greater gain for the school. Max Beckmann's art was showcased in exhibitions in Basel and Zurich later this year, and will be on display in Paris and America next year. It is already represented in almost all important museums." (Quoted from: ex. cat. Max Beckmann. Frankfurt 1915–1933, Frankfurt am Main 1983, p. 333) A year later a dispute arose between Fritz Wichert, former director of the Mannheim Kunsthalle and director of the Städelschule since 1923, and Beckmann. Wichert had hired the artist in 1925, but he began to accuse him of a lack of presence in Frankfurt. Beckmann wanted to protect his freedom and resigned on October 26, 1931. However, the Frankfurt mayor Ludwig Landmann, as well as Max Michel, head of the Department of Cultural Affairs and the director of the Städel, Georg Swarzenski, intervened; Beckmann remained professor in Frankfurt. For Beckmann, however, this wave of success was soon disrupted. It is true that Hildebrand Gurlitt in Hamburg and Herbert Kunze in Erfurt were planning another exhibition of Beckmann's works for the spring of 1933, and Ludwig Justi, director of the Nationalgalerie, set up a separate room for ten Beckmann paintings at the Berlin Kronprinzenpalais, which, as part of a general rearrangement of the works, was presented to the public on February 15. In early July, both the Berlin presentation and the Erfurt exhibition were canceled by the order of the National Socialists.

In the midst of extensive planning and an emotional rollercoaster, Beckmann began to work on his first triptych in Frankfurt in May 1932, in which he combined various symbols of existence. After its completion in Berlin in 1935, the individual panels were initially given innocuous titles such as "The Castle", "Homecoming", "The Stairs", while Beckmann only later came up with the highly visionary title "Departure". "The two spheres of enslavement of man and the dawn of freedom are irreconcilably contrasted. During the Nazi era, this work also had to be seen as an allegory of the political situation in Germany," said Stephan von Wiese, co-editor of the Beckmann letters, in his introduction . (Max Beckmann, Briefe 1925–1937, p. 12) In a conversation with Lilly von Schnitzler, Beckmann collector and patron, in February 1937, Beckmann explained the subtle content of the three panels: “What you see on the right and left is life . Life is torture, all kinds of pain - physical and mental pain. On the right panel you see yourself trying to find your way in the dark. You light up the room and staircase with a miserable dim light, as part of yourself, you drag along the corpses of your memories, your misdeeds and failures, the murders everyone commits at some point in their lives. You can never free yourself from your past, you have to carry this corpse while life beats the drum." ["And the center panel?" Frau von Schnitzler asked.] "King and queen, husband and wife, taken across the river by an unknown ferryman wearing a mask, he's the mysterious figure that takes us to a mysterious land. ... King and queen have freed themselves from the torments of existence - they have overcome them. The queen carries the greatest treasure - freedom - as a child on her lap. Freedom is what matters – it is the departure, the new beginning." (Max Beckmann. Die Realität der Träume in den Bildern, Leipzig 1987, p. 129) Beckmann's collector and friend Stephan Lackner and his New York gallerist Curt Valentin acquired the triptych "Departure" in 1937 and gave it to the Museum of Modern Art in an exchange in 1942.

It is obvious that Max Beckmann was well aware of the intentions the new rulers had. In anticipation, he rented an apartment in Berlin in January 1933. After Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Beckmann lost his post at the at the ‘Municipal School of Applied Arts’ in Frankfurt in March 1933. After around 18 years, Beckmann and his wife Mathilde left Frankfurt and moved to Berlin. The Beckmanns occasionally left the big city and its political tensions and visited Mathilde Beckmann’s sister Hedda in Holland, where she lived with the Dutch organist Valentijn Schoonderbeek, or they traveled to Ohlstadt, south of Murnau, to visit family.

On the occasion of the opening of the "Haus der deutschen Kunst" (House of German Art) on July 18, 1937, Hitler delivered his programmatic speech in which he declared modern art "degenerate". Concomitant threats prompted the Beckmanns to leave Germany and to emigrate to Holland, where they settled in Amsterdam. The confiscation of his works in museums in July and the defamation in the exhibition "Degenerate Art" in Munich undoubtedly supported his decision to live in exile. Despite the complicated everyday life, the following ten years in Amsterdam were tremendously productive. A rebellion against the forces of degradation, the unspiritual, the inhumane. It is not only his Amsterdam works that directly reflect the tremendous perfidy with which the National Socialists had been terrorizing their own country and also its neighbors for years. Between quotations from literary dramas and interpretations of ancient mythology, Beckmann hides his messages in everyday painting and describes the confusing distortions of the world. Even in his early works, Max Beckmann felt he had to work up the horrors of world history and depicted the events on vivid theater stages in his pictures, such as the industrious work of the sawyers in the present work. The loss of virtues made Beckmann a cynical interpreter of the events after World War I. Beckmann never gave up addressing current events, on the contrary, even when his new Amsterdam home was under the control of German troops, he noted in his diary on September 22, 1940: "If you consider all of this – the entire war or life as nothing but a scene in the theater of infinity, it is much easier to bear." (Max Beckmann, Tagebücher, 1940–1950, Munich 1955, September 22, 1940)

Käthe Rapoport von Porada

Nevertheless, this undoubtedly unusual painting immediately enthused the equally unusual Käthe Rapoport von Porada. She collected Beckmann's works and also traded them. The "Holzsäger im Wald" was also in her possession, it seems likely that she had acquired them from Flechtheim even before the exhibition.

The fashion journalist Käthe von Porada, née Magnus (Berlin 1891 - Antibes 1985), grew up in Berlin, and came into contact with theater- and literary circles, such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Gerhart Hauptmann and Arthur Schnitzler as a young woman. In 1911 she married the wealthy Viennese landowner Dr. Alfred Rapoport Edler von Porada and lived with him in Vienna. After they separated, she lived in both Vienna and Frankfurt am Main, where in 1924 she would eventually find an apartment on Untermainkai 21, just opposite from Beckmann's first place in Frankfurt with the Battenbergs, on the other side of the river Main. She wrote fashion reports for the Frankfurter Zeitung and gained access to the circle around the editor Heinrich Simons, which included luminaries like Thomas Mann and Max Beckmann. There are different stories about the first encounter between Beckmann and Porada. According to Porada's memoirs, she was present when Beckmann met his future wife Mathilde von Kaulbach in Vienna at the home of the Motesiczky family. (Marie-Louise von Motesiczky became Beckmann's master student in the mid 1920s.) Käthe von Porada would take on an important role in the artist's life. In 1928 she moved to Paris as a fashion journalist for the Ullstein publishing house and the Frankfurter Zeitung. For Beckmann, who regularly stayed in Paris at that point, she was very helpful: she found an apartment and a studio for his lengthy stays, helped him organize his daily life, and in 1930 introduced him to the influential poet and writer Philippe Soupault, who wrote an essay about Max Beckmann on the occasion of the exhibition at the Galerie de la Renaissance. In times of persecution and exile, von Porada was a reliable, loyal friend to Beckmann and helped him and his wife to prepare their move into exile in Amsterdam in 1937. Together with the American Stephan Lackner, collector, author and friend of the artist, von Porada organized an extensive exhibition of Beckmann's works in Bern in 1938, which was subsequently shown in Winterthur, Zurich and Basel. She was in contact with publishers and art dealers, among them I. B. Neumann in Berlin and Günter Franke in Munich. When a planned Beckmann show at Galerie Alfred Poyet in Paris was canceled for political reasons shortly before its opening in 1939, Porada decided to show his watercolors in her private apartment on Rue de la Pompe. At the outbreak of World War II, she found shelter with friends in Monte Carlo, where she remained until 1946. After a brief return to Paris, she settled in Vence near Nice until her death.

And Käthe von Porada was also a lender for the exhibition "Twentieth Century German Art" at the Burlington in London (fig.). With this exhibition, English, French and German artists and art lovers protested against the defamation of German art by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937. Influential personalities at the time, such as Herbert Read, writer, philosopher and editor of the Burlington Magazine, the Zurich-born painter and art dealer Irmgard Burchard and the writer, collector and art critic Paul Westheim, who had already emigrated to Paris at that time, were in charge of the exhibition of around 300 works from July 7 to August 27, 1938. About half of the exhibits came from German emigrants and artists defamed as "degenerate" by the National Socialists. In order to avoid putting the artists at risk, mainly loans from museums and private collections were shown. On July 21, 1938, Max Beckmann delivered his famous lecture "Meine Theorie der Malerei". Of the six works by the artist two, namely the "Holzsäger im Wald" and "Hafen von Genua" from 1927 (fig.), were contributed by Käthe von Porada, while three works, including the triptych "Versuchung" came from the collection of Stefan Lackner (fig.). [MvL]

Headquarters

Joseph-Wild-Str. 18

81829 Munich

Phone: +49 89 55 244-0

Fax: +49 89 55 244-177

info@kettererkunst.de

Louisa von Saucken / Undine Schleifer

Holstenwall 5

20355 Hamburg

Phone: +49 40 37 49 61-0

Fax: +49 40 37 49 61-66

infohamburg@kettererkunst.de

Dr. Simone Wiechers / Nane Schlage

Fasanenstr. 70

10719 Berlin

Phone: +49 30 88 67 53-63

Fax: +49 30 88 67 56-43

infoberlin@kettererkunst.de

Cordula Lichtenberg

Gertrudenstraße 24-28

50667 Cologne

Phone: +49 221 510 908-15

infokoeln@kettererkunst.de

Hessen

Rhineland-Palatinate

Miriam Heß

Phone: +49 62 21 58 80-038

Fax: +49 62 21 58 80-595

infoheidelberg@kettererkunst.de

We will inform you in time.