303

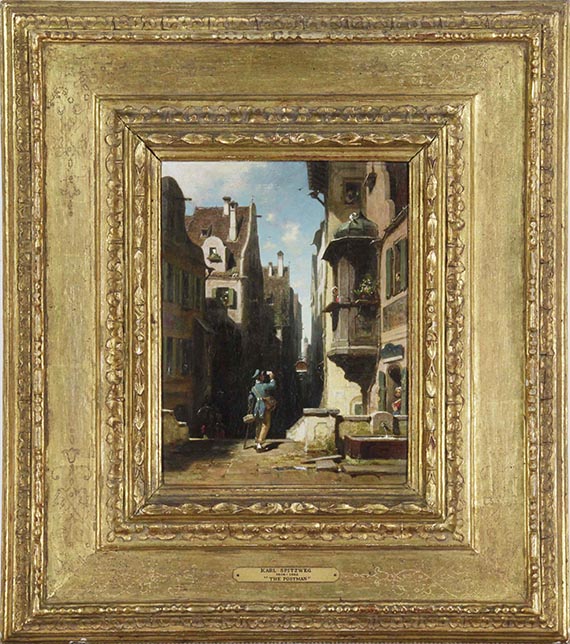

Carl Spitzweg

Der Postbote, Um 1860.

Oil on panel

Estimate:

€ 280,000 / $ 288,400 Sold:

€ 355,600 / $ 366,268 (incl. surcharge)

Der Postbote. Um 1860.

Oil on panel.

Lower left with the signature paraph. 27.2 x 20.8 cm (10.7 x 8.1 in).

• Romantic motif: letters and secret messages are of central importance in Spitzweg's oeuvre, who was an incessant letter writer and postal traveler himself

• A sophisticated narrative composition through the meaningful details

• Spitzweg's pictorial worlds show his mastery of architectural representation and spatial effects

• Special version from the series of mailmen with a view of Spitzweg's beloved azure sky.

We are grateful to Mr Detlef Rosenberger, who examined the original work, for his kind support in cataloging this lot.

PROVENANCE: Private collection (since 1926 family-owned).

Private collection Baden-Württemberg.

LITERATURE: Sotheby's, London, 19th Century European Paintings, including German, Austrian and Central European Paintings, and The Scandinavian Sale, June 31, 2006, lot 31 (fig.).

Oil on panel.

Lower left with the signature paraph. 27.2 x 20.8 cm (10.7 x 8.1 in).

• Romantic motif: letters and secret messages are of central importance in Spitzweg's oeuvre, who was an incessant letter writer and postal traveler himself

• A sophisticated narrative composition through the meaningful details

• Spitzweg's pictorial worlds show his mastery of architectural representation and spatial effects

• Special version from the series of mailmen with a view of Spitzweg's beloved azure sky.

We are grateful to Mr Detlef Rosenberger, who examined the original work, for his kind support in cataloging this lot.

PROVENANCE: Private collection (since 1926 family-owned).

Private collection Baden-Württemberg.

LITERATURE: Sotheby's, London, 19th Century European Paintings, including German, Austrian and Central European Paintings, and The Scandinavian Sale, June 31, 2006, lot 31 (fig.).

In the sketchbook of 1858, Spitzweg mentally formulated the pictorial narrative, which he subsequently executed in different versions: "Entry of a mail coach into a small town .. all the girls just looking out of the windows or otherwise .." (cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 269). He sketched the figure of the letter carrier with a parcel under his arm and the letter in his raised hand with great love of detail and in back view, in front of which one can imagine the scene with the expectant recipient. According to a note in a letter written around 1860, he also prepared several sketches of this subject. He arranged the scene in different variations with the essential elements: in the foreground, the young messenger in the bright blue fashionable uniform, holding the letter ready for delivery. The girls and ladies already wait in the windows and doors, curious and full of anticipation, perhaps hoping for a new summer hat, which the round parcel, reminiscent of a hatbox, promises, or a greeting from the hand of their beloved one. Which one might be chosen by the letter carrier, who certainly knows how to enjoy the attention? The hatbox could go to the two fine ladies approaching from the left of the staircase, the love letter presumably to the young woman in the bay window decorated with roses and lovebirds. Not without irony, Spitzweg gives the letter carrier a crutch in this version, perhaps referring to an earlier war wound or a potshot at the slowness of mail delivery.

Spitzweg arranges the scene in the small town as if on a stage. Here, too, the central location is a small square with a fountain, from which the view into the narrow alley leads into the depths, with the typical Spitzweg summer sky in bright blue behind it. Spitzweg artfully interlaced the small pictorial space with the houses. At the beginning of the 19th century, the rural exodus had brought many people to the cities where they had to live in confined circumstances in houses with narrow doors, raised windows, balustrades and bay windows. Views in and out of the windows enriched everyday life, and Spitzweg also observed the rich repertoire of entertainment from the window of his Munich apartment.

During the summer months, Spitzweg was constantly on the move, keeping a record of his discoveries in his drawings and sketching in Memmingen, Bad Tölz, Augsburg, Innsbruck and Bolzano in southern Germany and Tyrol. He often positions himself on the market square, the center of the small towns in front of the church or town hall, where people met. The tangle of façades, gables, staircases and windows of architecture that has grown over the centuries in a somewhat arbitrary and unplanned way, seems to be of particular artistic interest to him. In the architectures in his works, the most diverse styles and epochs also merge, low medieval houses, from which chimneys, dormers and archways grow, duck next to massive baroque towers and curved gables. This results in light and dark angles, shadows and brightly lit areas that lend the buildings a certain liveliness.

The private sphere is of particular interest in the art of Romanticism and the Biedermeier period. In this scene, the private and the public merge and will certainly give rise to conversations among the young girls. Spitzweg's paintings are often "window reports" in which the individualization and introspection of the Biedermeier period, the observation and exchange about the emotional world and human interaction, are the central theme. The written exchange in the form of letters, in which not only the ladies provide deep insight into their emotions and celebrate the commonplace in narrative and description, plays a particularly important role. It is precisely the secrecy of the sealed letters, which spur curiosity, and the knowledge of relationships offers wide scope for imagination. Spitzweg repeatedly addressed the theme of the delivery of letters, at times accompanied by obstacles such as watchful chaperones, which leads to curious scenes as in "Der abgefangene Liebesbrief“ (The Intercepted Love Letter, 1855-60, Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt), in which the young beau ropes the letter down two storeys. Although the delivery by post is safer, it is also accompanied by more attention and is less romantic.

Apart from going on extensive walks, Spitzweg's most frequently used means of transportation was the stagecoach that took him across the country to the most remote places. He experienced its arrival, which brought travelers, parcels and letters and always caused quite a stir, at close range. He also captured the excitement of this event in several works alongside the more subtle letter carrier scenes. It is precisely these journeys that are so exemplary of Spitzweg's communicative, narrative style of painting, about which he in turn communicates in countless, almost daily letters to family and friends. Everyday observations, moods, reports on the weather, trivial and amusing things are in a constant flow. His fellow humans provide him with the best entertainment: "I found a very amusing company in the carriages, who chatted all the way to Wasserburg in the most amusing way, so that I didn't even need to open the mail." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, September 1, 1839, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 26). Being constantly on the road is no obstacle to his correspondence: "Happily arrived here, I hasten to greet you. I live privately next to the post office. There are 2 beds in my room, so that if you wanted to come one day, you could stay right there. - How are you? How are Nani? Eugen and Otto? Don't keep me waiting long, and write me something on a piece of paper, just nothing bad." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, from Partenkirchen, August 1844, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 27). If his letters were not replied promptly, he would complain: "I have inquired and yet received no letters - Mr. Brother, you are a stinking lazy bitch! Thank God, if nothing else keeps you from writing to me but your laziness - then I'll be satisfied again." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, Verona, July 8, 1832, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 23). Waiting for news from loved ones, friends and relatives and the redemptive joy when the letter carrier appears seems to have been something Spitzweg experienced first-hand. [KT]

Spitzweg arranges the scene in the small town as if on a stage. Here, too, the central location is a small square with a fountain, from which the view into the narrow alley leads into the depths, with the typical Spitzweg summer sky in bright blue behind it. Spitzweg artfully interlaced the small pictorial space with the houses. At the beginning of the 19th century, the rural exodus had brought many people to the cities where they had to live in confined circumstances in houses with narrow doors, raised windows, balustrades and bay windows. Views in and out of the windows enriched everyday life, and Spitzweg also observed the rich repertoire of entertainment from the window of his Munich apartment.

During the summer months, Spitzweg was constantly on the move, keeping a record of his discoveries in his drawings and sketching in Memmingen, Bad Tölz, Augsburg, Innsbruck and Bolzano in southern Germany and Tyrol. He often positions himself on the market square, the center of the small towns in front of the church or town hall, where people met. The tangle of façades, gables, staircases and windows of architecture that has grown over the centuries in a somewhat arbitrary and unplanned way, seems to be of particular artistic interest to him. In the architectures in his works, the most diverse styles and epochs also merge, low medieval houses, from which chimneys, dormers and archways grow, duck next to massive baroque towers and curved gables. This results in light and dark angles, shadows and brightly lit areas that lend the buildings a certain liveliness.

The private sphere is of particular interest in the art of Romanticism and the Biedermeier period. In this scene, the private and the public merge and will certainly give rise to conversations among the young girls. Spitzweg's paintings are often "window reports" in which the individualization and introspection of the Biedermeier period, the observation and exchange about the emotional world and human interaction, are the central theme. The written exchange in the form of letters, in which not only the ladies provide deep insight into their emotions and celebrate the commonplace in narrative and description, plays a particularly important role. It is precisely the secrecy of the sealed letters, which spur curiosity, and the knowledge of relationships offers wide scope for imagination. Spitzweg repeatedly addressed the theme of the delivery of letters, at times accompanied by obstacles such as watchful chaperones, which leads to curious scenes as in "Der abgefangene Liebesbrief“ (The Intercepted Love Letter, 1855-60, Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt), in which the young beau ropes the letter down two storeys. Although the delivery by post is safer, it is also accompanied by more attention and is less romantic.

Apart from going on extensive walks, Spitzweg's most frequently used means of transportation was the stagecoach that took him across the country to the most remote places. He experienced its arrival, which brought travelers, parcels and letters and always caused quite a stir, at close range. He also captured the excitement of this event in several works alongside the more subtle letter carrier scenes. It is precisely these journeys that are so exemplary of Spitzweg's communicative, narrative style of painting, about which he in turn communicates in countless, almost daily letters to family and friends. Everyday observations, moods, reports on the weather, trivial and amusing things are in a constant flow. His fellow humans provide him with the best entertainment: "I found a very amusing company in the carriages, who chatted all the way to Wasserburg in the most amusing way, so that I didn't even need to open the mail." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, September 1, 1839, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 26). Being constantly on the road is no obstacle to his correspondence: "Happily arrived here, I hasten to greet you. I live privately next to the post office. There are 2 beds in my room, so that if you wanted to come one day, you could stay right there. - How are you? How are Nani? Eugen and Otto? Don't keep me waiting long, and write me something on a piece of paper, just nothing bad." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, from Partenkirchen, August 1844, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 27). If his letters were not replied promptly, he would complain: "I have inquired and yet received no letters - Mr. Brother, you are a stinking lazy bitch! Thank God, if nothing else keeps you from writing to me but your laziness - then I'll be satisfied again." (Spitzweg to his brother Eduard, Verona, July 8, 1832, cited in Wichmann 2002, p. 23). Waiting for news from loved ones, friends and relatives and the redemptive joy when the letter carrier appears seems to have been something Spitzweg experienced first-hand. [KT]

303

Carl Spitzweg

Der Postbote, Um 1860.

Oil on panel

Estimate:

€ 280,000 / $ 288,400 Sold:

€ 355,600 / $ 366,268 (incl. surcharge)

Lot 303

Lot 303